NORTH BENNINGTON — It could be said that Michelle Samour’s art begins on the molecular level.

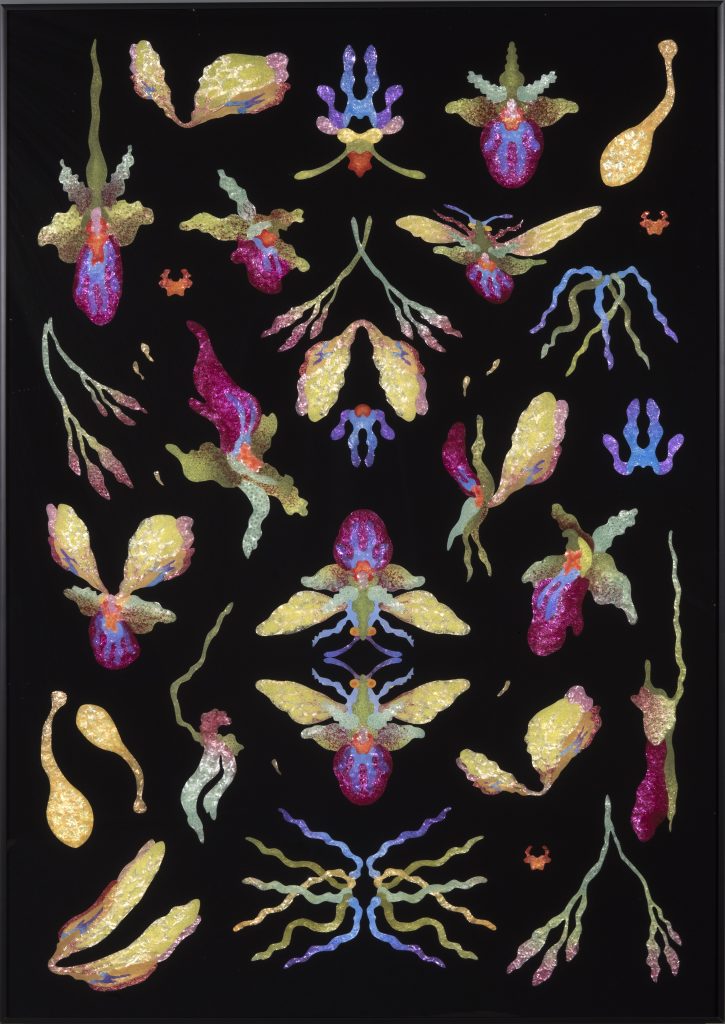

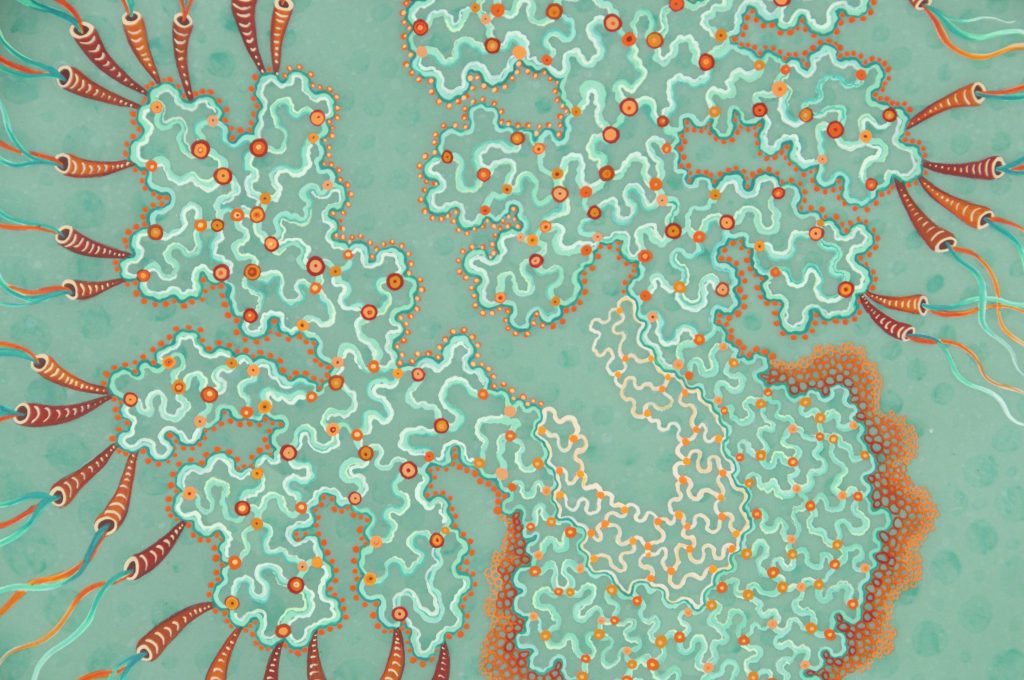

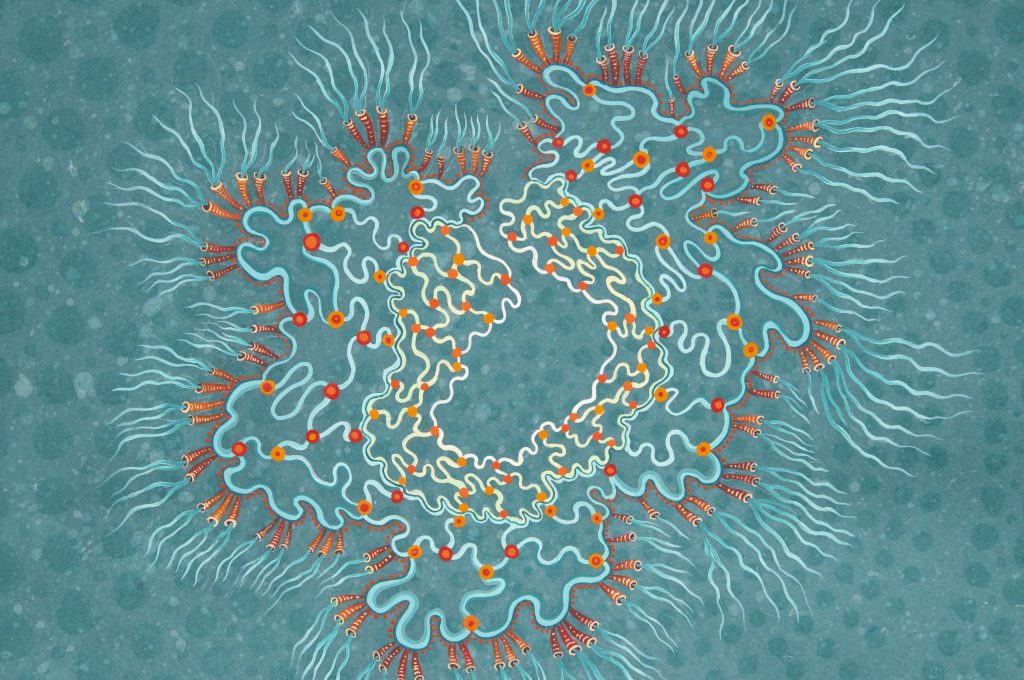

In her studio in North Bennington, she walked Vermont Country through the process of papermaking, from fiber to pulp to drying into molds or sheets or other shapes that resemble the natural world. The shapes and textures that adorn her studio walls call to mind plants, mushrooms, and unidentifiable specimens one might find under a microscope (which she also has in her studio).

“When you’re working with paper, you’re part cook, and you’re part scientist,” Samour said. “There are measurements.

There’s understanding the chemistry. There’s a lot of chemistry involved.

Not only am I telling stories about the natural world and the biologic world, I am using materials that come from that world.”

Samour is a nationally-recognized interdisciplinary artist whose work incorporates painting, drawing, collage and more. Her paintings summon insects, microorganisms and Persian rugs. On her website, there are photos from a series called “Borders and Boundaries,” inspired by her Palestinian heritage. The series includes a piece that, using acrylic Mother of Pearl and paper pulp, depicts the shapes of Israel, Palestinian territories and encroaching settlements as biological specimens.

“It’s talking about borders and boundaries, the potential for movement and relating that to biology and biologic form,” she said.

In a book of drawings in her studio, her finely detailed works incorporate various elements of nature: a bird with leaves for wings, mating snails from which sprout what appears to be an aquatic plant formation, and other images that are surreal but don’t seem that far-fetched.

Samour moved to Bennington from the Boston area two years ago, and her studio, adjacent to the Bennington College campus, was built over a year ago.

“What was surprising was that when we moved here, I hadn’t realized that Bennington had a real connection to the paper industry,” she said. Local history includes the artist Ken Noland, who worked with colored paper pulp in a converted barn studio near the Park-McCullough house, and the Stark Paper Mill, which was down the street from Samour’s studio.

Samour took the time to not only give a demonstration of her process, but talk about how she got into papermaking, how her family inspired her, and how her work captures the collision of science, human rights and curiosity.

Q: The themes of biology and human rights are consistent in your work. Can you talk about how this came to be?

A: Part of that interest has to do with the fact that my father was a research chemist. So having grown up with him, taking trips to the lab. He’d do little experiments with us. My parents were also really interested in the natural world. My mother’s side of the family was French and my French grandmother lived with us. I remember going out and hunting for mushrooms at a young age and picking watercress.

My father’s side of the family was Palestinian. I remember as a child asking him, when he told me that our family was Palestinian, I asked him to show me that on the globe, and he said it’s not there; it’s now Israel. I could not wrap my mind around that.

So over the years, I studied a little bit more about that area of the world. I thought that at some point I wanted to address that part of my heritage, didn’t know quite how to do it. I wanted it to be real honest. I wanted to take a really honest approach to telling that story. So I started, maybe seven years ago or so, working with different media to talk about the Palestinian story. The section on my website, “Borders and Boundaries,” talks all about that.

There was a strong family influence. And I think I’m just the kind of person, too, that likes to dive into things, and sort of, looking at the biologic world, what lies beyond the surface of something. Thinking about cellular structure, how something is formed, how something is constructed and built, that just has always intrigued me.

Q: You have described your role as a papermaker as “part cook, part scientist.” Can you talk about what it is like to work in this medium?

A: I just love getting my hands into pulp. Some people, when they look at the cooked fiber, like, “Oooh” (shudders). Most of my students, I would say, 99 percent of my students, for instance, love putting their hands in the pulp and cooking it and smelling it. But every once in a while, there would be someone who would touch it and I would just know that they were just not going to be coming back to the next class.

But that was very rare, because most people are totally seduced by the process of making paper. I still consider it to be very magical, very challenging, always surprises, always something new to learn. Despite the fact that I’ve worked with it for over 40 years, I’m always learning something new. I’m never bored with it.

And I appreciate the physicality of it. It’s such an immersive way of working. I sometimes think about it, like working with clay, except that you know, with clay, you put it in the kiln. With paper, you put it in the drying box, and it changes when it dries, so you don’t quite know what you’re gonna get until it’s fully dried, until you’ve finished working with it. But it is a lot lighter than clay.

Q: How did you get into papermaking?

A: My first exposure to paper was as a child. My father brought me to MIT, where he had gone to school. There were some models that were made by Dard Hunter, who was a papermaker. He was really responsible in the West for bringing the knowledge of hand papermaking to people. I mean, he did a lot of research on Eastern papermaking and Western papermaking and wrote about the history of paper making.

Anyway, he had made these beautiful, intricate models. And I remember vaguely, I mean, I was really a little kid when I saw them, but they stuck in my my mind. Then, in junior high school I did a paper on papermaking. I’m assuming it was for a science class. I don’t remember. But I remember just being totally taken with the idea that you could make it. I mean, we use paper all the time. We touch paper constantly. But rarely do we think about how it’s made and where it comes from.

I mean it is again, the paper tied back to plant matter because it is plants. So then, I was doing some collage work after finishing art school, and I was taping materials onto some heavyweight paper, but the paper was still buckling. So I started recycling paper and embedding the materials into the paper. That was the first time that I actually had used it in my artwork.

And that was a real revelation. It just started all of my interest really and using it as an art form. And at that time in the that was in the mid-’70s. It was really, a very new medium for artists, and artists were gathering around the country sharing ideas. There was very little being taught on the college level. So we would all gather and share information, and it grew from there.

Q: You’re working on a book with coauthor Lynn Sures. What is the book about?

A: It’s about papermaking as an art form, and it’s about the history of artists who have really, radically changed how we think about paper as a substrate. So: these artists, looking at history, and looking at the contemporary work — there will be a lot of contemporary work in the book, as well, of artists who are using it as a primary medium.

It’s very exciting. There have been other books that have touched on this in different ways, but ours will be something different. It’s such an exciting medium. One of the reasons to do it, too, for us, was that not that many people know that much about paper.

If you look at any of my work — well, if I don’t tell you about it, I wouldn’t imagine if you just saw this [gestures to her work], that you’d know exactly what it was, right? And that’s what I love about it, too, is that people expect paper to look like what they think paper should look like, which means paper that they’ve drawn on, or maybe it’s fine art paper. But when it looks like something else, people, they don’t know what they’re looking at. We want to inform people and get them excited about this medium, and share what other people have been doing with this medium for 60-plus years as an art form.

For more information about Samour and her art, visit her website, michellesamour.com.

Gen Louise Mangiaratti, is editor of Vermont Country magazine and is arts & entertainment editor for Vermont News & Media. She lives in Brattleboro with her cat, Theodora, and welcomes your post-idyllic holiday music recommendations at gmangiaratti@reformer.com.