By Gordon Dossett, Vermont News & Media correspondent

Editor’s note: This column, part of an occasional series, previously ran in the Manchester Journal.

MANCHESTER CENTER — Do we locals ever act as tourists at home? A tourist dives into some of the best spots of a place, eager to experience what it has to offer. Too often, we locals — OK, I’ll speak for myself — too often I settle into a routine and skip the places tourists travel hours to seek out. I decided to be a tourist in the Northshire, and see what I was missing.

First stop: The American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester Center. By chance, this turns out to be an excellent moment to visit the museum since it has just finished rebranding. Maybe the word “rebranding” needs rebranding, but really at heart it’s an exercise in identity. Who are we? What have we been and how can we be better going forward? Organizations (and individuals?) who fail to stop and take stock risk becoming the next Sears, Atari or Zenith.

We can see the issue of identity in stark relief if we go back to the original artwork used by the museum in the late 1960s and early 1970s: Singular white man, old-fashioned get-up, old school rod and reel — nostalgia for white men, perhaps, but not exactly an embrace of the sport going forward. This logo was discarded long ago.

The recent rebranding effort took about a year, Executive Director Sarah Foster told me, with those involved concentrating first on core values and attributes (water, fish, fly, as well as the preservation of fly fishing history and artifacts, and an appeal to a wide audience). The group then moved on to how those aspects could best be illustrated.

She showed me several competing examples for the logo. The group liked the shield, which implied protection. Trustee Adam Trisk, in his blog about the rebranding, notes the museum sought a vibrant color palette, suggesting waters.

Leaders emphasized the acronym. Just as Kentucky Fried Chicken morphed into KFC 30 years ago, the American Museum of Fly Fishing, perhaps more tradition-bound, just now sought out the snappier AMFF (11 syllables down to four), an acronym not as graceful as a fly line floating through the air. Well, maybe — if you pause: AM … FF. But never mind. The acronym was widely used by members, according to Foster, so emphasizing it seemed right.

But let’s get to the museum itself, shall we? While the museum is close to the Orvis Flagship Store and has its support, it is a stand-alone entity, not an auxiliary operation of Orvis. At the museum, I was greeted by Bob Goodfellow, a hale, well-met fellow and a former arts director at National Geographic magazine. His dog, Emme, is also part of the welcoming team, sometimes pacing back and forth outside, even in snow. Bob gave me the general layout: collection of fishing-related art, Joan and Lee Wulff exhibit, library upstairs. The space is modern, fresh and airy — in short, welcoming.

Gordon Dossett — For the Manchester Journal

Before I get into the exhibits and other aspects of the museum, let me admit something: I’ve gone fly fishing maybe three times in my life, the last time 20 some years ago, and the most I caught was low-hanging foliage. Although I marvel that a person can tie a fly smaller than a kernel of popcorn, my typical day is not devoted to thinking of, much less participating in, fly fishing.

I’m sure fanatics, who know their wet flies from nymphs and dry flies, will approach the museum differently than me, a fishing bumbler.

Go into the art collection. Right off, you’ll see a painting by Edward Lampson Henry from 1873 titled “Fishing by the Stream,” a bucolic scene of some well-dressed people, dog nearby. Look closer, and you’ll see that the inept, citified man has snagged his dog, not a fish — causing passersby to glance over. The painting suggests a differing perspective on humor in 1873; most of us today wouldn’t find piercing a dog with a hook a real knee-slapper. But as the placard suggests, we see the tensions of people in those days striving — and failing — at getting back to a more “natural” state.

This tension also emerges in Robert Robinson’s painting “Fly Fishing” (1933), depicting a mechanic who, in the process of towing a car (background) has taken a moment to park his tow truck and cast a line into the stream, to the consternation of a policeman in the background. As the placard states, “At the height of the Great Depression, the image of a mechanic longing to reconnect with the natural world would have resonated with viewers.”

Women are depicted in the collection, albeit in context of their times. One painting, “Tossing Trout” (1949), is by James Montgomery Flagg, the artist who drew Uncle Sam proclaiming, “I Want You for U.S. Army.” This painting pictures a smiling, kerchiefed woman jauntily flipping a fish in a frying pan (fish flying rather than fly fishing). The painting reinforces sexist tropes of the time: She’s doing the cooking, she’s happy about it, and she even has her lipstick on out in the woods.

There are other paintings of sylvan scenes: fishing man and stream painted in soothing greens and blues. I found myself drawn not just to the fishing depicted, but what the paintings suggested about people — the artist and the subjects.

The next room is devoted to Joan and Lee Wulff, “basically royalty,” as Bob says. Google Joan and Lee Wulff and up will pop 608,000 results. They get just an inadequate paragraph here. The Wulffs personified brilliance in fishing. A short film running on a loop depicts Lee Wulff pulling in three fish on one cast. (Ask Bob how the hell he did it.)

Lee invented the fly fishing vest and the concept of catch and release. An exhibit shows tiny flies that Lee tied, calling for dexterity not found in mere mortals. In 1991, Lee sadly died of a heart attack at 86 — while flying his plane. Joan lives on, spry at 96, in New York’s upper Beaverkill Valley, still teaching fly fishing. She has taught so many for so long, that one observer points out there is a little Joan Wulff in the casts of thousands of people in streams around the world. In the film loop, she’s depicted casually reeling in a fish, making a challenging move seem effortless. She still holds records for distance — made when she entered competitions against only men — and accuracy in casting. One museum professional described Joan this way: “She’s a badass.”

To understand what was on display at the museum, I talked to Kirsti Scutt Edwards, collections manager. (Full disclosure: Kirsti is a neighbor and friend.) As she showed me the many boxes and shelves holding material that had come in over the years, I gained a sense of the huge scope of her work. For example, the museum houses hundreds of books related to fishing, the oldest of which goes back to 1597.

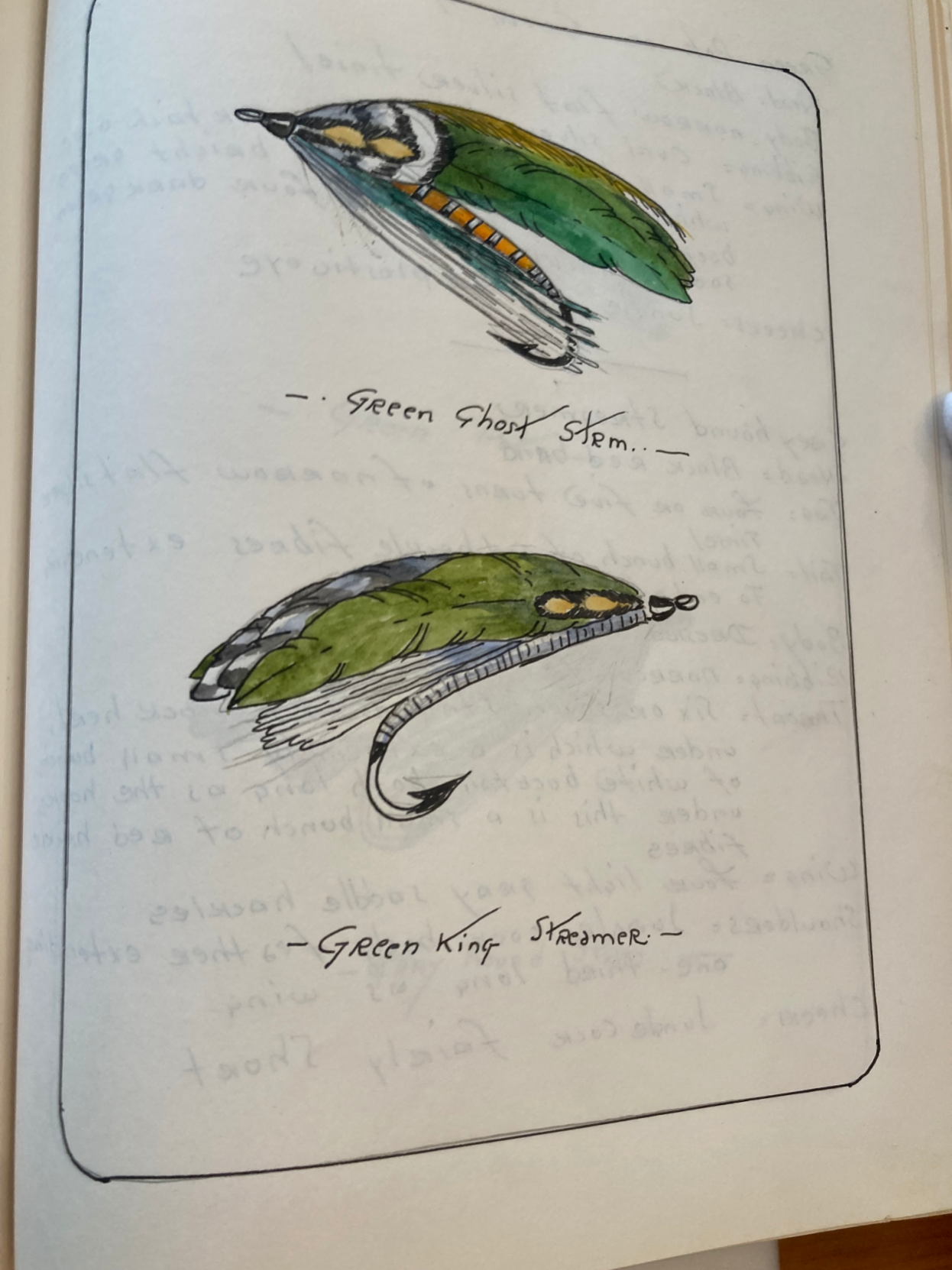

Gordon Dossett — For the Manchester Journal

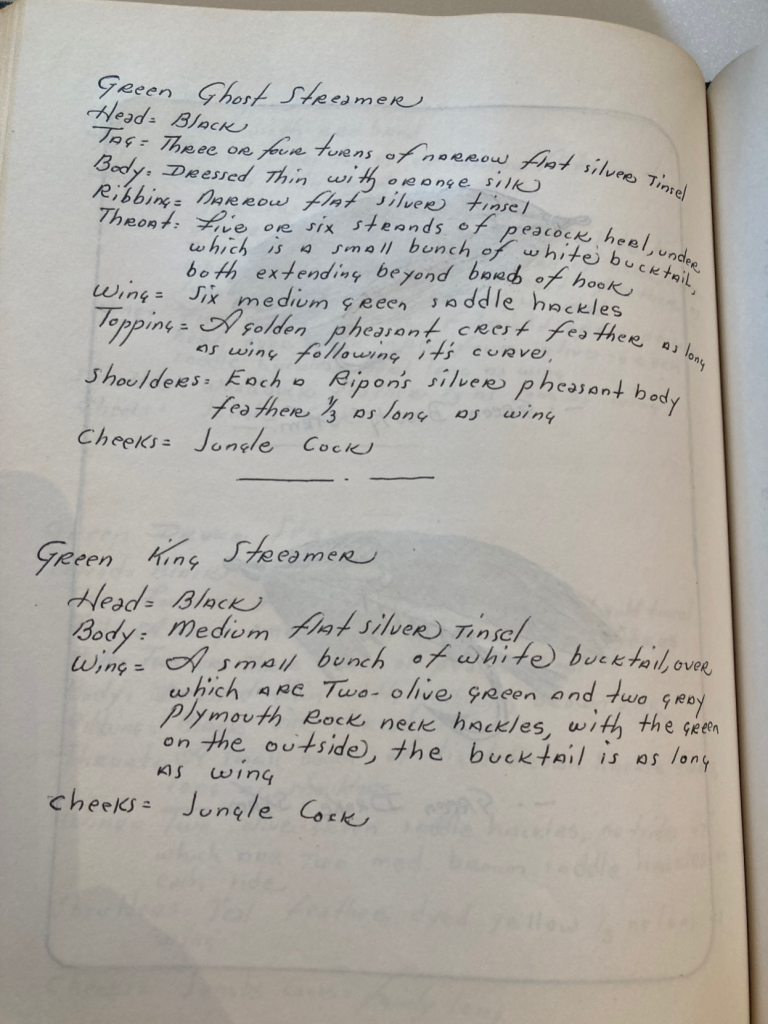

She showed me fascinating sketchbooks by Casimir Naleway, which had come in as part of a large collection. Naleway filled sketchbooks, usually one sketch a day, sometimes with detailed explanations. These sketches of flies are minutely detailed — sometimes in black and white, sometimes in color, and the explanations are precisely expressed with not one word crossed out in hundreds of pages. The entries suggest a highly organized and disciplined mind, a person who took great satisfaction in detailing flies for the act itself, with no thought of publication.

But the museum knows little about him. He is thought to have worked in the steel mills of Chicago, and kept notebooks from the 1940s to 1970s. (So: challenge to readers — just who is Casimir Naleway? My Google search uncovered a Casimir Casey Naleway (maybe?), but nothing further. Note: The work of the mysterious Mr. Naleway is not now on display, but who knows about the future?)

Kirsti’s days are not all spent in search of mysterious illustrators. Only 5 to 10 percent of the collection, she estimates, is on display. The museum constantly receives donated private collections, which she catalogs so that future museum workers can find items and consider them for exhibitions. She’s also part of the team that determines which artifacts become part of an exhibit, the Joan and Lee Wulff Exhibition being an excellent recent example. Sometimes a piece is too large and simply doesn’t fit in well with the other pieces being displayed. For that particular exhibit, the museum had many more artifacts than could go on exhibit.

So here are some reflections. Do you need to know or even care much about fly fishing to appreciate this museum? Surprisingly, no: I was drawn not so much to the intricacies of flies and fishing techniques. I’m sure that anglers would find displays fascinating on another level, one that I couldn’t appreciate. I was drawn more to the people passionate about the sport. There is a beauty to lives lived as the Wulffs did, immersed and excelling in what to them was a calling. Further, the displayed art is beautiful in itself and gives insight into history.

My recommendation: Be a tourist. Go to the museum when it opens, maybe on a Thursday. Pet the friendly dog at the door. Talk to Bob. (He has a big name tag saying Bob, and he could fill in as Santa in a pinch.) Get a tour, if he isn’t busy. And then treat yourself to lunch somewhere and ponder the wonders you’ve seen.

Gordon Dossett traded the traffic and urban ugliness of Los Angeles for the Green Mountains. He lives with his teenaged children, a cat and a dog, packing urban sprawl into one home. He likes making to-do lists and losing them.