County was stumped by mysterious disappearance and presumed slaying of Russell Colvin by the brothers Boorn

By Lex Merrell

Vermont Country

MANCHESTER — Two brothers, Stephen and Jesse Boorn, grew up in Manchester in humble circumstances and supported their families with hard labor.

Their problems began in the early 1800s, when their sister married Russell Colvin, a man of weak intellect and an even weaker work ethic. Some believed Colvin was deranged. He was unable to support their sister and her children, so that duty fell to Stephen and Jesse.

Colvin would disappear for months at a time without any warning, leaving his family penniless.

Burdened with the responsibility of taking care of Colvin’s increasing number of children, the brothers and Colvin turned conversations into arguments and then escalated to physical aggression. The cycle would often repeat itself.

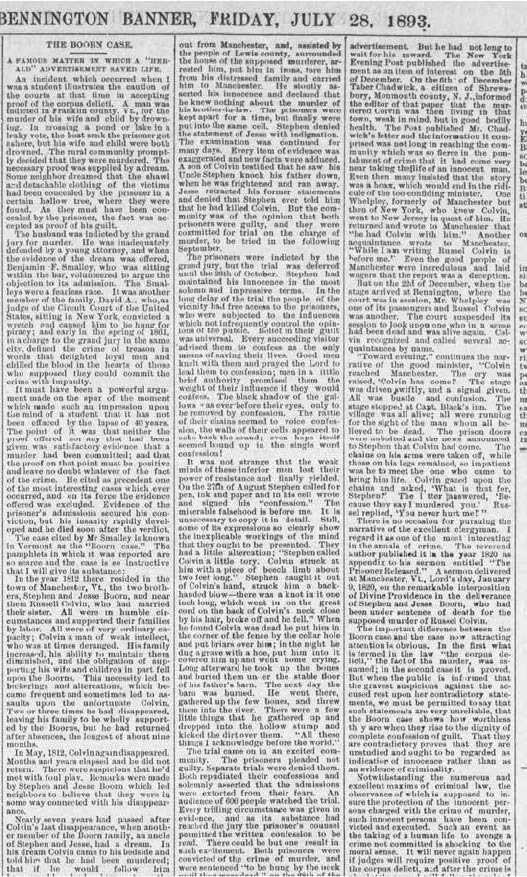

In May 1812, Colvin disappeared again. This time, years went by, and neighbors of the Boorn family became wary of the brothers because of comments made after Colvin’s disappearance.The brothers made it sound like Colvin wasn’t coming back.

After seven years and no sign of Colvin, a Boorn uncle was cursed with a series of dreams. In these dreams, or visions as some called them, Colvin loomed over his bedside and revealed that he was murdered. He begged his uncle to follow him to his final resting place.

Eventually, the uncle gave in and cautiously walked to the burial site. It was 4 feet by 4 feet and was originally used to bury potatoes.

The pit was excavated. A large jackknife and a button were found. Before setting eyes on the items, Russell’s wife could describe them. The items were undoubtedly her husband’s.

After this discovery, a young boy with a spaniel dog walked past the Boorn father’s home. The dog went wild when he smelled a decaying stump in front of the house.

The dog began to dig and bones began to rise to the surface. Broken and burned bones were found alongside human toenails.

An amputated leg, buried four years prior to the unearthing of the bones, was exhumed for comparison. The bones weren’t human, but it was determined that they were added to the pile to deceive anyone who uncovered them.

As for the bones being burned, a member of the community remembered that after Colvin’s disappearance, the Boorn father’s barn burned to the ground. Stephen and Jesse also burned a large log heap on the property.

Theories on the Colvin murder began to flow. The theory was that the brothers burned Colvin’s body in the log heap, and then burned what remained in the barn.

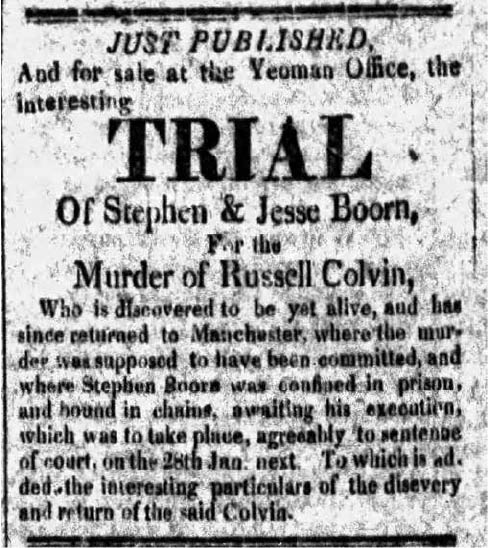

Soon after the discovery, the Boorn brothers were arrested for the murder of Russell Colvin.

As the stress of a murder charge and trial set in, Jesse Boorn had a confession to make: Stephen Boorn admitted to him the murder of Colvin. Jesse, in a trembling voice, repeated the story Stephen told him.

Stephen and Colvin got into an argument, as they had so many times before, and when it got physical, Colvin tried to run away. To stop him, Stephen hit Colvin in the head with a rock or club, and fractured his skull.

In the years since the murder, Stephen Boorn moved 200 miles away to Lewis County, N.Y. When the people of Lewis County discovered there was a murderer in their midst, they surrounded his home. Boorn was dragged out of his house in irons, torn from his family and carried back to Manchester to stand trial.

Despite Jesse Boorn’s story, Stephen Boorn consistently declared his innocence after capture.

Evidence for the trial was gathered, added and exaggerated. Jesse Boorn eventually recanted his accusation against his brother, but Colvin’s son testified that he saw the murder take place.

The court of public opinion was clear: The Boorn brothers were killers.

While they were locked up, the public had free access to the prisoners. Everyone who visited them urged them to confess to avoid a death sentence. Men of God prayed in front of them to let the Lord lead them to a confession.

The pressure on the brothers mounted until, on Aug. 27, 1819, Stephen Boorn confessed. He admitted that their argument got physical. Russell hit him, he hit back, and Colvin fell down, dead.

Stephen hid Colvin’s body under a mound of greenery until nightfall when he could bury the body in secret. A few years later, he unearthed the body and reburied the bones under the barn. The barn burned down the next day. Stephen dug up the bones for a final time and threw them in the river. He hid what remained of the corpse in the tree stump.

When it was time, the brothers were denied separate trials. They pleaded not guilty, stating their original confessions were made in duress. But it wasn’t long before they were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

The community of Manchester wanted Jesse Boorn to live out the rest of his days in prison, but there was no mercy for Stephen. His death was set in stone.

A month prior to Stephen’s scheduled hanging, a clergyman, the Rev. Lemuel Haynes, went to pray with Stephen. Again, Boorn declared his innocence and begged the reverend to pray for him. For the first time, Stephen Boorn’s story was believed. Haynes wanted to prove his innocence.

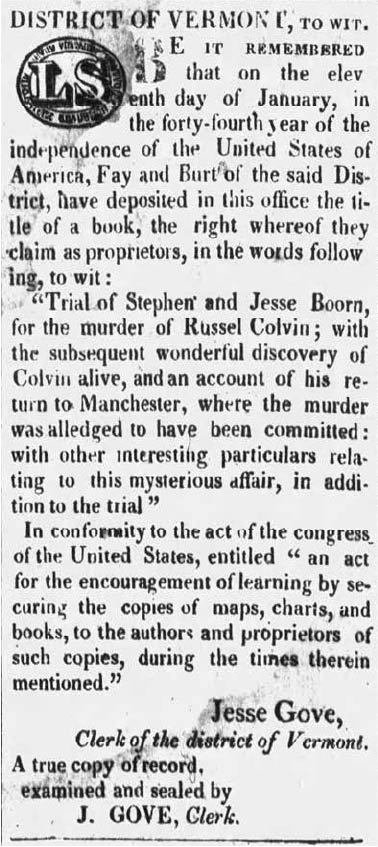

Although Haynes was poor, he spent some of the little money he had to put a letter in a newspaper, asking if anyone had proof of Stephen’s innocence. After being ridiculed by the town for spending money on such a foolish errand, The (N.Y.) Evening Post published the letter.

The very next day, Tabor Chadwick of New Jersey sent word that Colvin was living in his town. He was still weak-minded but very much alive.

Rumors spread, and disbelief set in. Bets were placed on whether or not the gossip was true.

Bones were found, a confession was signed, two men were convicted of murder, and one was to be hung. Brought back to Vermont, Colvin gazed upon Stephen in shackles, pointed at the iron around his wrists and asked, “What’s that for?”

No one has been able to confirm what Colvin was doing in a small town in New Jersey. It seemed like even Colvin was unsure of how he got there.

As the good Rev. Haynes retold this story about divine intervention on Jan. 9, 1820, he called the sermon “The Prisoner Released.” It stands as a warning on the dangers of presumed guilt in the court of public opinion.

Lex Lecce — spends most of her time working, but any of her free time is spent with her family — mostly her new husband and cats. Her search history worries her therapist.