By Danielle M. Crosier, Vermont Country Magazine.

BENNINGTON — Inside of the Bennington Museum, rests the weathered gravestone of Jedediah Dewey – first reverend to the small community of Benning Wentworth’s “Bennington.” The headstone, an original, is stained and worn and cracked – from either some long ago impact, or the simple result of a naturally occurring fracture – and it represents much.

To museum curator Jamie Franklin, director of collections and exhibitions at the establishment, the gravestone represents a very important piece of early Vermont history. To him, the stone was the impetus for a personal quest, sparking a decades-long interest in learning about the man who carved it – and his contemporaries.

“I kind of dove deep into the early gravestone carvers that were working here,” said Franklin, detailing how his initial inquiry ignited what became a passion. Franklin now hosts cemetery crawls – at least one, if not two, guided annual two-hour tours through the historic 18th and 19th century stones of the Bennington Centre Cemetery, which was established in 1762.

Together with his friend and colleague – historian and preservationist William Hosley of Connecticut, who recently passed away – Franklin spent years learning about the techniques, lives, and styles of Vermont’s first gravestone carvers.

“[Hosley] was a museum curator, and he loved early New England gravestones,” explained Franklin of his former compatriot. “When I first started getting into this, he would say that New England cemeteries are like open air museums. If you’re talking about material culture from the 18th century, gravestones probably have the highest survival rate of any objects that were created and used – and they’re the most public because they are literally out in the public and anybody can walk through the cemetery and look at them. I love the idea of these early gravestones and cemeteries being these open air museums.”

The Bennington Centre Cemetery – also known as the Old Bennington Cemetery – is Vermont’s oldest official cemetery and sits atop the hill on which the museum resides. It is just one of many old graveyards in the county to hold significant historical information within the gravemarkers alone.

The Bennington Centre Cemetery site hosts the graves of at least 75 soldiers who fought in the Battle of Bennington in 1777; the author of Vermont’s Declaration of Independence and later Constitution, Jonas Fay; five Vermont governors; the poet Robert Frost; and scores of 18th century graves with headstones carved by notables like Zerubbabel Collins and his son James, brothers William and Peter Buckland, Gershom Bartlett, Josiah Manning and his sons Rockwell and Frederick, Ebenezer Soule, Roger Booth, and Samuel Dwight.

In West Sandgate, “old timer” Jane Eisenhart rummaged through her closet to unearth about a dozen or more long scrolls. Unfurling them each in turn, Eisenhart reminisced about her pastime of grave rubbing, which took place over two decades in the 1990s and 2000s. Similarly to Franklin and Hosley, Eisenhart succumbed to the allure of the Soul in Flight effigies – present on the majority of latter 18th century gravestones in the area.

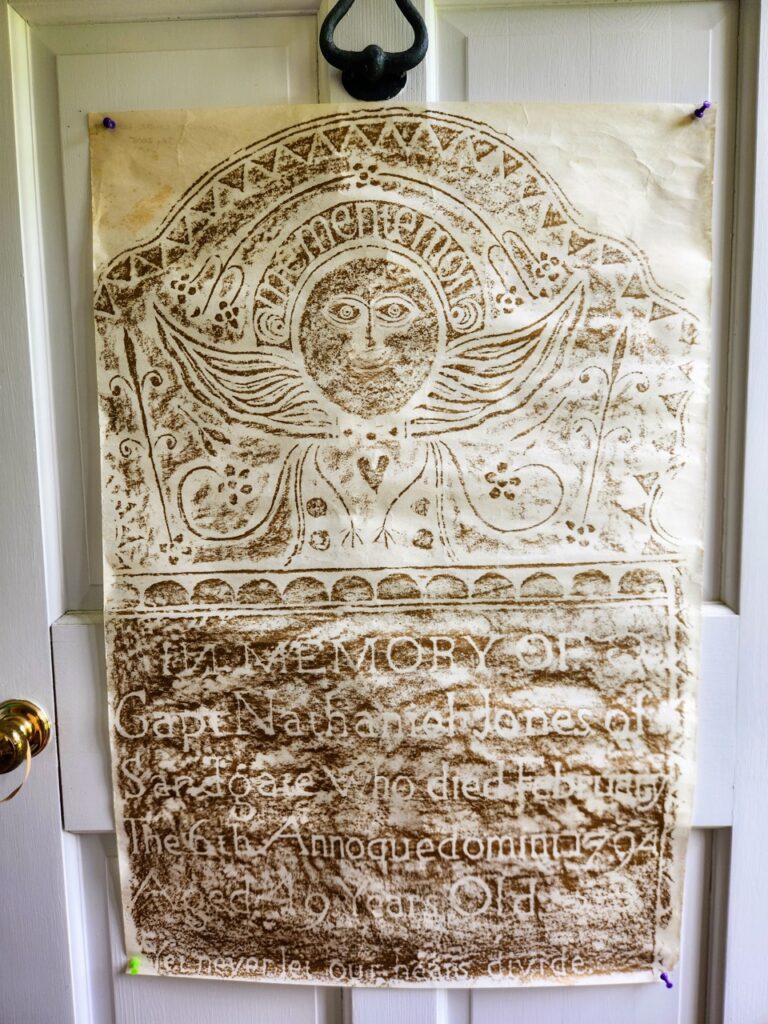

Carefully tacking each rubbing to the front door to better see it in natural light, Eisenhart shed light on what attracted her to the pastime – it was just a calling, “I don’t remember why I got interested in them, but I did a lot of them – mostly in Sandgate, but some further away. And, I saved them. And, here they all are. I’ve got a lot of them, and I just did them because they were so beautiful – and they’re such fun,” said Eisenhart, rummaging through the selection to find the notes that she took on the back of each of the rubbings. “And who knows what I was up to in those days. I don’t remember.”

“This one is from October 27, 1994, from West Sandgate. And this one is from Center Cambridge, October 26 1995. This is North Bennington October 1994. This one is Center Shaftsbury. Huh, October,” mused Eisenhart, examining the rubbing of yet another Soul in Flight gravestone. It seemed they were nearly all rubbed in the month of October, but with varying years. And, all were Souls in Flight.

The soul of one had a torso attached, and little skinny arms with tiny hands. At the top, it read, “O! Relentless Death.” Below that, it read, “In memory of Grace Nichols, the amiable consort of Mr. Nathaniel Nichols who died February the 26th AD 1796 in the 26th year of her age. In virtue old, in years but young.” The “th” was written atop the word “year,” and there was no space between “her” and “age.”

Another inscription Eisenhart noted was more along the same lines, but elaborated, “In virtue old, in years but young, was the corpse that here doth lie. In her both sense and beauty shown, alas that she must die. Her last distress with patience bore, severely was she try’d. The saints sustained her grief and pain, but still the woman died.”

“This one,” laughed Eisenhart, unfurling another. “In memory of Mrs. Lucretia Beardslee wife of Mr. Levi Beardslee who died November the 30th AD 1801 aged 42 years. Depart my friends dry up your Tears Here I muft lie till crift Appears.” The spelling and script included errors, miscalculations in spacing, and the “long s” in numerous places, but not consistently. The AD had a uniquely unconventional flourish to it.

“In MEMORY of Mr. John McCool who died Dec.r 23rd 1798. In the 83rd Year of his Age,” read Eisenhart, continuing, “All you that read, With little care. Who walk away, and leave me here. Muft not forget, that you muft die And be Intomb’d as well as I.”

Again, the wording, lettering, and Soul in Flight seemed oddly unplanned, childlike, and a bit whimsical. Another held a backwards upper case N, other odd spellings and punctuation, superscript and subscript letters, letters added atop other words, and a forgotten letter added with an arrow to indicate its correct placement. One spoke of love, another of the death of a young boy “with the Small-Pox.”

“And, this one – ‘MOMENTO MORI In Memory of Cap’t Nathaniel Jones of Sandgate who died February the 6th Annoquedomini 1794 aged 49 years old. Yet never let our hearts divide.’ Ooooo,” said Eisenhart, pointing out what she called “little chicken legs” on the Soul in Flight, as well as a tiny heart and the odd spelling of Anno Domini. She also saw two pitchforks with little flowers on the ends. She mused, laughing, “Interesting, these people – and their doggerel poetry.”

“And, you know, it’s unusual that the carver puts his name on the stone,” said Eisenhart, rolling up the scrolls and storing them neatly back in their box. “That is rare. There’s just one or two in Shaftsbury that I know have somebody’s name on them – but you practically never see that.”

If the names Zerubbabel, Gershom, and Ebenezer Soule don’t speak to the unique character of these 18th century gravestone carvers, perhaps their stones will bear the weight.

All of the aforementioned gravestone carvers worked in the area, carving some of the earliest gravestones in the state. All worked during the period where gravestone styles were rapidly evolving from the the Plain Style, a brief and unadorned, puritanistic description of the facts; to the Death Head Style, with a winged skull symbolizing the looming death that faces all; to the Soul in Flight Style, representing the journey of the soul to the afterlife that awaits only the righteous; to the later Urn and Weeping Willow Style, representing the remains returning to dust and the sorrow that accompanies loss. Each of these styles symbolized the rapidly and dynamically shifting landscape of the settlement of western New England, and of the fleeting nature of the time period that they served.

Although all working on similar themes, these early Southern Vermont gravestone carvers each developed a distinctive style, similar to folk artists whose work is often identifiable through the individual techniques present in their craft.

Zerubbabel (pronounced Zarubba-BEL) Collins was one of Franklin’s favorites.

Zerubbabel Collins, son of Connecticut gravestone carver Benjamin Collins, came to the Southern Vermont area in 1778, purchasing a farm in Shaftsbury. From there, he excised white marble slabs from his own quarry, and set up shop. He worked prolifically, producing at least 40 identified gravestones in the Town of Bennington and at least 30 identified gravestones in the Town of Shaftsbury.

In all, Zerubbabel Collins produced over 300 gravestones between Connecticut and Nova Scotia – including the signed gravestone of the Manchester Vampire, Rachel Burton, whose body was exhumed from its resting place at Manchester’s Factory Point Cemetery, just two years after her death. Due to illness in the village, and in a feverish belief that she must be a vampire coming back to haunt her husband and his new wife, the townsfolk removed her heart, liver, and lungs, and burned them in the local forge of blacksmith Jacob Mead. Her body was reinterred under the stone carved and signed by, “Z. Collins, Sculp.”

In the graveyards of Southern Vermont, the work of Zerubbabel Collins is characterized by elaborate filigree and floral patterns surrounding the effigy of the Soul in Flight. His souls have rather large and prominent jaws and deeply incised faces. The wings are relatively small in comparison with the wings of some from his contemporaries. Zerubbabel Collins was purported to have an apprentice named Benjamin Dyer – and his son James Collins eventually took over the business, continuing the family profession briefly after his father’s death.

Other notable 18th century gravestone carvers included Gershom Bartlett; Josiah, Rockwell, and Frederick Manning; and Samuel Dwight – all of whom immigrated to or passed through what would become the Southern Vermont area from Connecticut, just as Zerubbabel Collins did. The time period was turbulent. Life was difficult. The Age of Enlightenment and the Revolutionary War were wreaking their havoc, and “Vermont” was only just newly forming its identity.

Gershom Bartlett’s Soul in Flight work was characterized by a bulbous nose and wings that looked like either morel mushrooms or curling wave-like dips. He’s often called the “hook and eye carver,” due to the shape of the eyes and nose of his Soul in Flight carvings. His work often shows a downturned mouth, eyebrows over the eyes, and includes diamonds, a small heart beneath the legend, and four-leafed clovers. From 1773 to 1797, Gershom carved over 350 gravestones, although most can be found in the Windsor, Norwich, Newbury, and East Ryegate areas.

The Manning’s Soul in Flight work was characterized by differing styles based on time period, and who was interred beneath – for children, the wings were curved and sharply down swept; for the time period, the wings evolved from bat-like wings to feathered sweeps. The hair of the soul was often illustrated in a pompadour, or a series of side curls. The Manning brothers, Rockwell and Frederick, both soldiers in the Revolutionary War, developed their own style of carving with the use of Vermont’s white marble. In these, their soul faces and wings often protruded outward from the stones, rather than being etched or carved into them as was the case with many of the other early carvers.

“Samuel Dwight is another of my favorites,” exclaimed Franklin. “He came up here from Connecticut around 1790. He actually studied at Yale, and he came here as a school teacher. He had a number of different styles that evolved over time. He created these stones very early in his career that I referred to as the ‘stick figure style,’ and some of his earliest work can be seen in the Berkshires. You see a lot of his stones in Shaftsbury and Arlington. He had these little tiny hands that he did, and hearts. He was an interesting, interesting figure.”

Some of Samuel Dwight’s gravestone carvings have long hair with curled bottoms; others have skinny little arms with tiny hands holding flowers, or just splayed out like “jazz hands.” Dwight’s lettering is also distinctive, especially his use of an off-kilter ampersand and a distinguishably scripted AD (Anno Domini). His carvings are child-like and whimsical in their style, and one of Samuel Dwight’s gravestones that is especially poignant is found in the Bennington Centre Cemetery where sisters Laura and Marianne Swift are interred. The sisters died just days apart and are buried under a conjoined gravestone of two coffins, side by side. This is Samuel Dwight’s only known gravestone in the Bennington Centre Cemetery.

According to Nancy Jean Melin, contributor to David Watter’s “Markers IV: The Journal of the Association of Gravestone Studies,” Samuel Dwight died alone and penniless in his home in Sunderland, where an 1830 census record indicates that he traded his possessions – “one red cow, one feather bed and bedding” – to the town for continued support. His grave has never been identified, but his charming legacy lives on in his many fanciful works.

“I think early cemeteries and the gravestones therein are one of the best ways to connect with the history and culture of our region’s earliest settlers,” explained Franklin. “From the artistry of the carving, and the spirituality and theology of the epitaphs, to the stories inferred – such as the death, days apart, of two young sisters – cemeteries connect us with the past in a tangible way that is almost impossible to experience in any other way.”

With their wealth of historical and cultural inferences, preserved in the form of headstones and monuments, Franklin continues to see the cemeteries of Bennington County as “open air museums.” They offer a unique perspective into the lives of the earliest settlers to this region, and the carvers who lived here – and they detail the evolution of attitudes, beliefs, and values over time. They continue to reveal their secrets, even today.

In the case of the gravestone of Jedediah Dewey, Franklin explained, a surprising plot twist was revealed. When the crack first appeared, a decision was made to replace the historic and important landmark with a duplicate. The old damaged stone was removed from the concrete that it had been sunk in, and more writing was discovered. This writing revealed that the stone had not been carved by Josiah Manning, as originally believed, but was instead carved by his son Frederick. The stone was signed.

“It’s Frederick’s,” said Franklin. “The stone carving business was very much based on the kind of medieval apprentice tradition, and so a lot of these stone carver’s sons would apprentice with them. He would have been 21 right around the time that Jedediah Dewey died, so that was probably his ‘masterpiece’ – which is a term taken from the tradition where an apprentice would carve a really important work. And, that’s probably why it’s signed. He probably signed that piece because it was his way of announcing his mastery of the craft, and going out on his own.”

And, as for the myth of Benjamin Dyer being the apprentice of Zerubbabel Collins, historical documents have uncovered the truth (available in the Walloomsac Review Volume 8 2012). Dyer was simply a currier and tanner, but served as the executor of a will or the purchaser of a tombstone and the misinterpretation of text has forever muddied the waters – with many now convinced that Dyer was one of the great gravestone carvers of Southern Vermont.

Other mysteries remain. Franklin loves to explore the old cemeteries of Bennington County, looking for the telltale signs of each of the 18th century carvers, and delving into historical texts that knit together their stories and the stories of those interred beneath their stones.

The grave of Zerubbabel Collins, often cited as Vermont’s most prolific and important gravestone carver, can be visited in the Shaftsbury Cemetery. Ironically, his gravestone is carved in rather plain fashion with the Urn and Weeping Willow, rather than the elaborate floral scroll work and Soul in Flight that he will forever be remembered by. He died in the “64th year of his age,” although the brief text on his stone is now highly worn and weathered – and difficult to decipher.

Eisenhart, a member of the Vermont Old Cemetery Association, worries about the deterioration and degradation that weathering and time have taken on the old stones, “I go to the annual VOCA meetings where they talk about cemeteries and preserving them – and doing this stuff.” She waved a hand at the rubbings.

Her love and appreciation of the oldest stones is clear, “Always the face with wings. I think it’s the spirit of death. From this, I had my own tombstone carved. I found a man who carved tombstones. I went to him, and he bought a slab of Vermont marble, and carved me a tombstone. We designed it; he carved it. It’s in the Wallingford Cemetery, waiting for me.”

Eisenhart’s long term partner, who passed a number of years ago, is also waiting – but, it might be a long while yet before the two lie side to side once more. According to Eisenhart, the text of her gravestone still needs to be filled in with the date of her death, “It says ‘my name, who died in the’ – and then, it’s blank. Somebody’s going to have to put ‘in the 99th year of her life.”

To learn more about the cemetery crawls hosted by the Bennington Museum, visit benningtonmuseum.org/event/2025cemetery-tour. For a fairly comprehensive list of the over 100 old Bennington County graveyards, visit ldsgenealogy.com/VT/Bennington-County-Cemetery-Records.htm. And, to explore some of the old gravestones of Bennington County for yourself, simply get in your car and go.