By Mark Rondeau, Vermont Country Magazine.

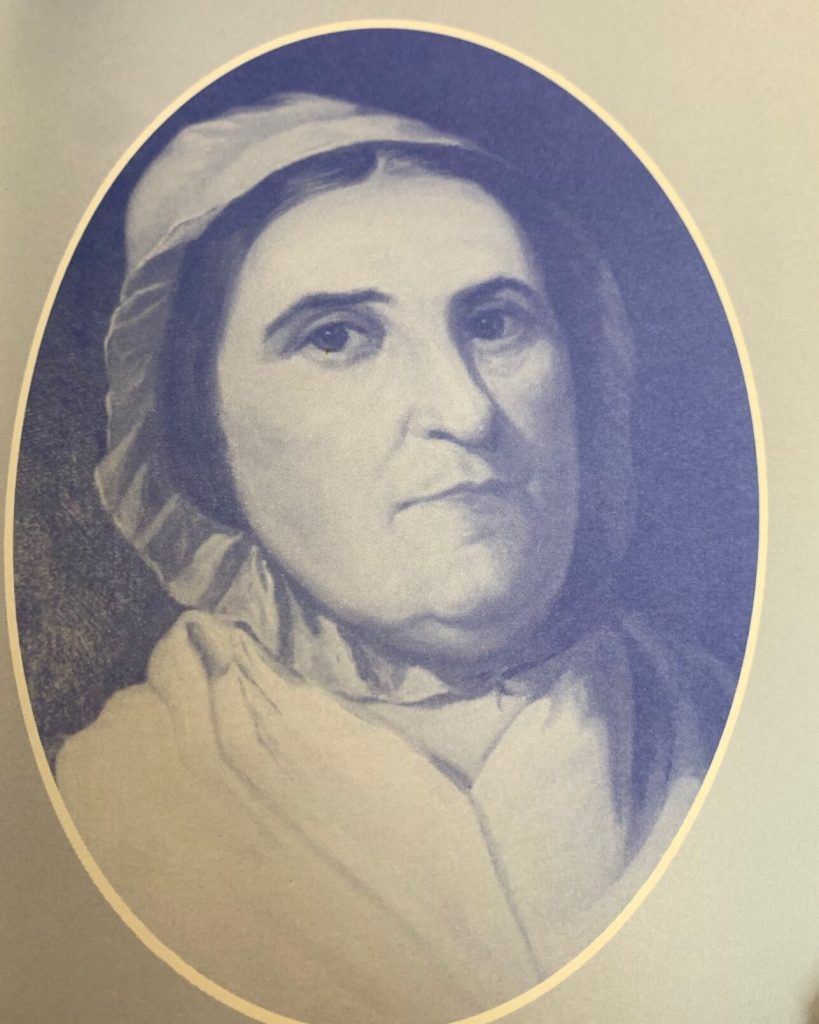

Behind the legend of Molly Stark stands a woman capable of running a farm by herself, entertaining prominent guests, serving as a sentinel in wartime, or shooting a treed bear.

She was also a woman clearly loved by her husband, for she was immortalized by words attributed to her husband at the Battle of Bennington.

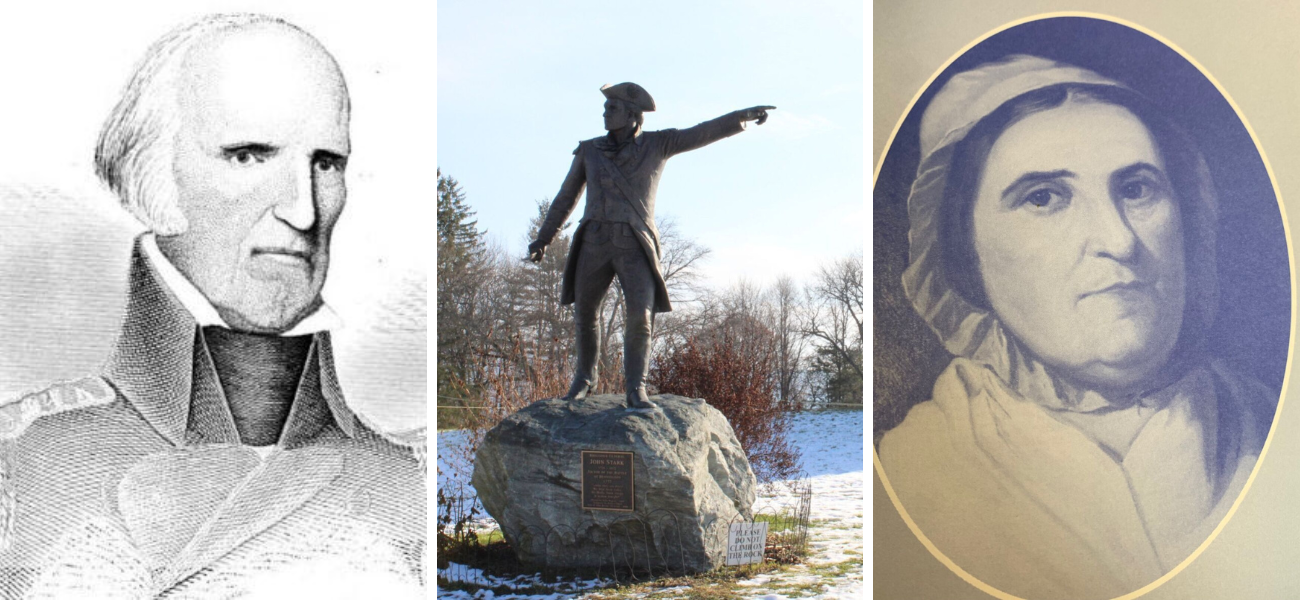

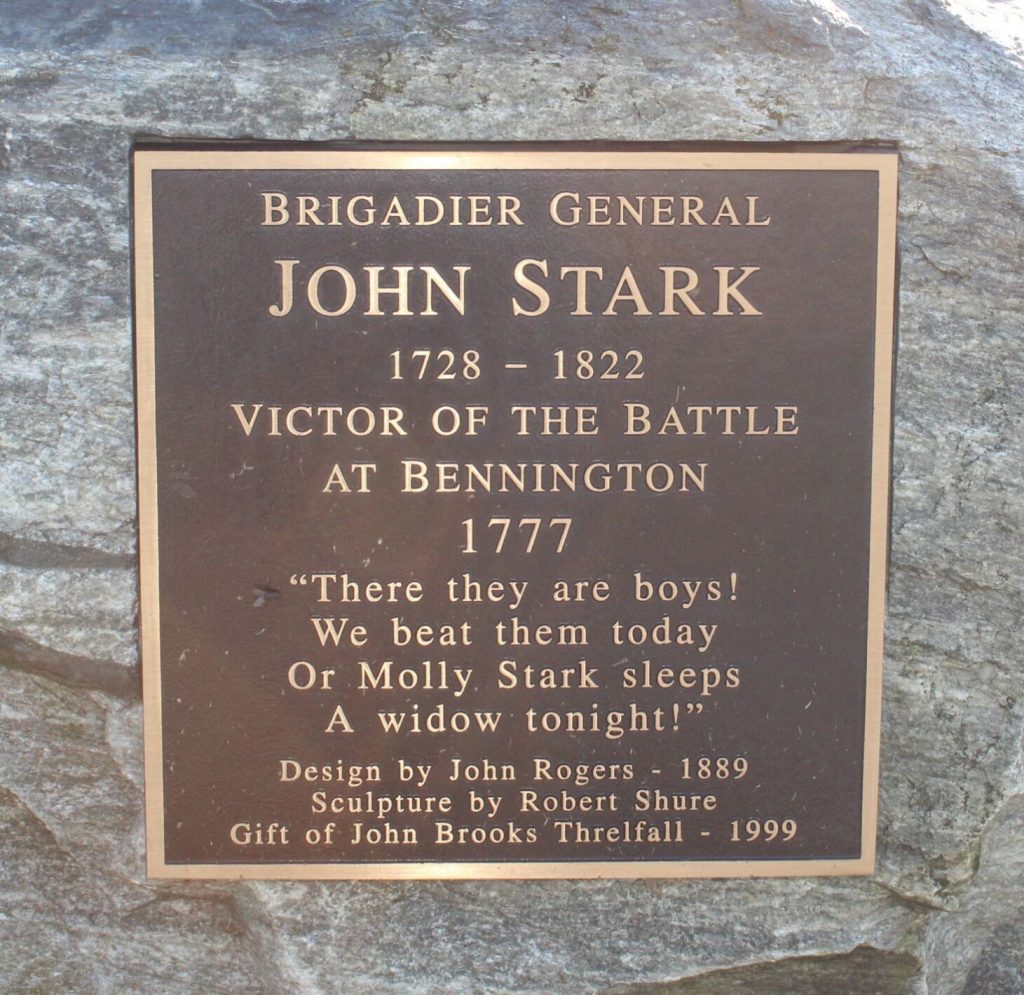

There are many versions of the words her husband, Gen. John Stark, victorious commander of the revolutionary army at the Battle of Bennington, is supposed to have said at the height of the fighting.

“Did Stark really say those words? You know the words, or you think you do,” author and local historian Phil Holland said at a talk at the Bennington Museum. “The first written reference that I found dates from 1819, in which Stark is said to address his troops with, ‘My boys, you see those red coats yonder, they must fall into our hands in 15 minutes, or Molly is a widow.’”

Another version has it, “There, my boys, are your enemies, the red-coats and Tories; you must beat them, or my wife sleeps a widow to-night.”

John Stark won the battle and Molly’s name has endured. Behind the name — a nickname, actually, was a woman just as real and admirable as her well-documented hero husband.

“The feeling that Molly is everywhere may also be due to her name on a school, a park, a trail, a mountain, a motel, a cannon, and a sanatorium in Stark County, Ohio,” Holland said.

Most of these named entities are in Vermont, even though historians doubt Molly ever set foot here.

“Her profile has changed, though, since the 19th century. From a passive role in a pithy, romantic utterance in which her husband is ready to die for his country and is thinking of her, to being celebrated for her own love, courage, and self-reliance,” Holland said.

The inscription on the Molly Stark statue in Wilmington, along the Molly Stark Trail (Route 9), indicates this change to a broader appreciation of the woman behind the legend.

“Wife of General John Stark, mother of 11 children, homemaker, patriot, and defender of the household. Her love, courage, and self-reliance were common virtues among the many hearty women of frontier New England’s 18th century towns,” reads the inscription. “This strength and devotion to husband, home, and family were virtues that sustained her, as well as so many women and their families, during those times when their husbands were called to duty for their country in the constant French and Indian Wars and the American Revolution.”

Massachusetts-born

A key source for the life of Molly Stark is the pamphlet “Molly Stark: a woman of great patriotism and courage” by Jane Elizabeth Stark Maney. She draws on both published sources and original documents.

Elizabeth Page was born in Haverhill, Mass., on Feb. 16, 1737, the daughter of Caleb and Elizabeth Page. “She was christened Elizabeth, nicknamed Betsey, and always called Molly by her husband,” according to Maney’s pamphlet. The family eventually relocated to New Hampshire.

Young John Stark was a comrade of Captain Caleb Page, Elizabeth Page’s father.

In 1753, Stark apparently expressed the desire to marry into Captain Page’s family because he’d heard the family brought good luck. Soon thereafter, the story goes, Betsey and John met at a barn-raising in Goffstown. John was a member of Rogers Rangers and away for extended periods, but they saw each other when he visited home.

They were married at her father’s house on Aug. 20, 1758. She was 21 and he was 30. After a brief honeymoon, John went back to duty with Rogers’ Rangers, a famous unit in the French and Indian War.

“Molly remained with her father and step-mother at the home in Dunbarton during the first three years of her marriage,” according to Maney. “John was away much of this time, and Molly had the safety and security of her father’s home. During this time, their first child, Caleb Stark, was born. Molly had two brothers and a sister who sometimes shared the home with her.”

Tragedy struck when Molly’s older brother Caleb Jr. was killed in the French and Indian War in the Battle on Snowshoes, which took place between Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point in New York on Jan. 21, 1757.

“Only 30 at the time of his death, his father, Caleb Page, was grief-stricken and never got over the loss of his son. Molly shared this overwhelming grief with the rest of the family,” Maney writes.

Farm and family

The French and Indian War ended in 1763, and the couple had more than a decade to devote to their growing family. This period ended when the Revolutionary War broke out and John Stark headed off to raise a New Hampshire regiment and join the fight. The couple’s son, Caleb, 16, also enlisted, as did another son later on.

A letter from John to Molly survives. He writes of comfortable quarters he has in Medford, Mass., the home of a Tory who joined the British in Boston. “I am waiting impatiently upon your presence here in Medford,” John writes. “I have a pleasant and sufficiently large room, called the Marble Chamber, that looks out over the garden. ‘Tis comfortable enough, but seems empty without Someone to share it.”

Molly visited her husband several times at his headquarters during fighting in eastern Massachusetts.

She even participated in the Battle of Copp’s Hill, in north Boston, in 1775. She was stationed on horseback by her husband to alert the countryside if her husband’s troops were fired upon.

“The wife of Colonel Stark was at this time in the camp on a visit, and was directed by him to mount on horseback, after the embarkation of the troops, and remain in sight to watch the result. If the party were fired upon, she was directed to ride into the country, spread the alarm, and arouse the people. The troops effected their passage over the river unmolested. She observed them land, advance up the height and take possession of the battery,” according to the book “Memoir and Official Correspondence of Gen. John Stark” by Caleb Stark, published in 1860. “The wife of General Stark has often related this incident.”

Still raising young children herself, Molly stayed home as the fighting moved west and lasted several more years. During the war, life was hard for women keeping the home front going. John Stark highlights this in the first sentence of the letter quoted above: “I trust you and the children are well, and that work on the Farm is progressing to your satisfaction.”

Smallpox was a common disease. Molly wished to be a pioneer in inoculating her family against the disease. Although the smallpox vaccine had not been invented yet, “people were experimenting by inoculating themselves with serum obtained from human victims,” Maney writes.

“Molly asked the General Court for permission to inoculate her children and her servants. Her petition was denied, probably because she was a woman,” Maney writes. “This request was finally granted when John Himself applied for permission.”

Another incident shows that erecting a statue of Molly with a rifle in Wilmington was no imaginative stretch.

“One night she was called upon to shoot a bear that had been treed by the family dogs near her house in New Hampshire. Molly, defending her family in the absence of her husband, shot the bear and instructed her farm help to carry it away.”

Joy and loss

When the war ended successfully in 1783, John and Molly settled back into family and community life in New Hampshire.

John generally eschewed public life and took care of his farm, where he and Molly raised their 11 children. The only exception he made was to attend town meetings. John reportedly gave nicknames to all the children, as well as to nephews and nieces.

Molly had a lively and independent nature. While she loved her husband, and helped counterbalance his tempestuous temper, she did not always obey him. “Her calm but firm way kept her husband from intimidating her on various occasions,” Maney writes.

While Molly enjoyed going out to weddings, christenings, and all sorts of gatherings, John often did not

“The family told the story of one event that Molly was planning to attend, against the wishes of her husband. John hid her best dress in the butter churn. Molly found another garment and went to the party alone, only to find upon arriving home, that he had locked her out of the house,” Maney writes. “She calmly got into the house through a window and greeted her husband warmly at breakfast as though nothing unusual had happened.”

Molly and John lived to see the births of numerous grandchildren and also several great-grandchildren. “Many of them lived at the Stark family mansion, a large and happy family,” Maney writes.

One granddaughter described Molly as always calm and composed: “a dignified lady.”

“John and Molly always had an annual ‘Harvest Home,’ a sort of good-will party for all their neighbors and friends. Like most parents, their lives revolved around their children and grandchildren. They never shrank for merrymaking,” Maney writes.

Molly nursed her husband through frequent bouts of rheumatism that were aggravated by his years of sleeping on the ground in all kinds of weather. She also frequently entertained influential visiting colonists, not surprising given her husband’s prominence. In 1809, the couple attended the inauguration of President James Madison.

Still, life was particularly hard in those days. Molly outlived six of her 11 children. She was healthy all her life until she contracted typhoid fever and died on June 29, 1814, at age 77.

The general took the loss of his wife of 56 years very hard. As her body was borne away from the house after her funeral, Stark, unable to follow, said, “Good-bye my Molly, we sup no more together on earth.” As more than one writer has noted with bitter irony, that night John Stark slept a widower.

The “Hero of Bennington” soldiered on until May 8, 1822, dying at age 93 in Manchester, N.H.

Mark Rondeau with Milo, his longtime companion and the first cat he adopted from Second Chance Animal Center in Arlington. Mark, is a long-time newspaper reporter, photographer and editor. He is interested in the outdoors, local history and baseball.