Poison parsnip and poison ivy, false hellebore galore … beware as you take to Green Mountain trails

By Jim Therrien

Vermont Country

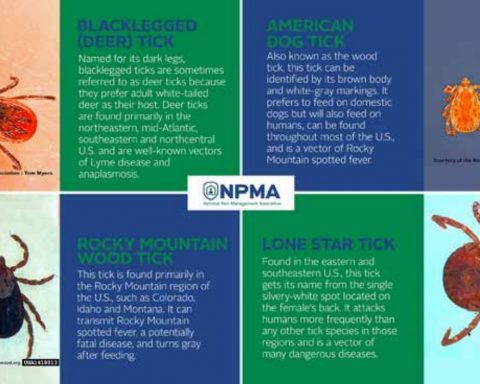

BENNINGTON — Tick season and Lyme disease get a lot of deserved attention in Vermont in the warmer months, but several wild plants offer their own nasty keepsakes to amblers in the Green Mountain State.

A surprising number of common plants can prove toxic to humans to some degree, and it pays to know what is sprouting in your yard, along roadways, beside hiking trails or in recreation areas, Vermont State Toxicologist Sarah Vose said.

In general, toxic or “poisonous” plants can be certifiably poisonous if ingested, or they can cause a skin rash or second-degree burns replete with ugly raised blisters.

FALSE HELLEBORE

False hellebore is poisonous if ingested and sometimes is mistakenly picked by foragers looking for edible ramps.

Early in the season, foragers looking for ramps in wooded areas don’t want to mistake false hellebore for the edible green-leafed plant. Ramps, Vose said, have an odor like onions or garlic, something the false hellebore lacks.

“Ramps are super-pungent,” she said.

In one recent summer season, there were 25 reports of people being treated at hospitals after ingesting false hellebore in Vermont.

“And that’s only those who were treated at hospitals,” Vose said. “There could have been many more.”

The white flowers of the Lily of the Valley also cause a serious reaction if ingested, she said, and a concern with the plant is that children might pick the pretty flowers or reddish orange berries and put them in their mouths.

PARSNIP, IVY

When you think about poison ivy, remember the old rhyme: “Leaves of three, let it be.”

More common around Vermont, and within the experience of many people, are the familiar wild parsnip and poison ivy.

Vost said the tall, yellow-flowered wild parsnip is commonly found in fields or along roadsides, and it causes a reaction when the plant’s sap comes

into contact with the skin. The reaction is triggered by sunlight — called photodermatitis, sun poisoning or photoallergy — and avoiding sun on affected areas after exposure can reduce the effects.

Furocoumarin is the chemical in wild parsnip that causes this plant to react with sunlight and damage skin.

DON’T BURN IT

“And who hasn’t had poison ivy?” Vose noted.

She cautioned that burning yard waste that includes poison ivy plants produces toxic smoke that is an irritant to the eyes or to the respiratory system.

According to the Mayo Clinic website, poison ivy usually requires only home treatment, which can include over-the-counter cortisone cream or ointment and application of calamine lotion.

If the rash is widespread or causes a lot of blisters, a doctor may prescribe an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone, to reduce swelling, according to the University of Vermont website.

For exposure to wild parsnip, the Vermont Department of Health recommends washing the skin thoroughly with soap and water as soon as possible, protecting exposed skin from sunlight for at least 48 hours, and calling a health care provider if the person experiences a skin reaction.

PROFESSIONAL PRECAUTIONS

For tree workers and landscapers, there’s no way to ignore poisonous plants, but Mike D’Agata, one of the owners of Greater Heights Tree and Land Management in Pownal, said the best advice he would give property owners is to just avoid it — and to cover your skin if you might be anywhere near poison ivy, poison parsnip or similar plants.

“Poison ivy is the big one, because it can climb up trees,” he said. “It can be ground cover; it can be a vine. We can get trees that are just covered in poison ivy. Lot of times you don’t notice it until you get into it.”

The white flowers of the Lily of the Valley cause a serious reaction if ingested, and a concern with the plant is that children might pick the pretty flowers or reddish orange berries and put them in their mouths.

A crew member once had to take two days off after poison ivy spread over his body, D’Agata said. “He was completely covered. Probably the worst reaction I’ve ever seen.”

On the other hand, D’Agata said some workers, like himself, could “roll around in it” and only get only a mild rash from poison ivy, although he has noticed he’s become more susceptible to the plant’s effects over the years.

For property owners, D’Agata urges caution when trying to rid areas of poisonous plants, since contact with the sap — picked up on clothing, mowing or cutting equipment — can result in a reaction later on.

His crew members are careful to immediately wash skin that might have been exposed, he said, and in their trucks, they carry packaged wipes that remove ivy or parsnip sap.

HIKER HAZARDS

Hikers often encounter toxic plants and should know how to deal with them.

Silvia Cassano, the co-chair of Bennington’s Appalachian Trail Committee, said she recommends learning to identify wild parsnip and other poisonous plants and advises wearing “pants and/or gaiters covering their ankles. Long-sleeve shirts can help (plants can be tall).”

She adds, “If you walk through anything poisonous, the sap/oils could be on your shoes and gaiters. I always wash my hands after removing gaiters, and I inspect them for seeds.”

If skin blisters appear, Cassano said, “Do not rupture for as long as possible and seek medical attention.” She encountered hikers in Bennington County who “had a terrible rash on their shins and had to go to urgent care.”

In the Bennington area, she said, there is wild parsnip in the grassy area where the Appalachian and Long trails cross Vermont Route 9 in Woodford, as well as on both sides of the tunnel under Route 279 on the Bald Mountain Trail to the White Rocks.

Pets, too, can pick up the plant’s sap. “Give your pet a bath if you think they came in contact with plant sap or oil, so the plant oil does not spread to you through touch or surfaces,” Cassano said.

A poster alerts hikers and others to the possibility of poison wild parsnip in the area.

Jim Therrien — reports for the three Vermont News Media newspapers in Southern Vermont. He previously worked as a reporter and editor at The Berkshire Eagle, the Bennington Banner, The Springfield Republican and the former North Adams Transcript.