Town, Abenaki tribe land National Park Service grant to benefit culturally sensitive site

By Susan Smallheer

Vermont Country

BELLOWS FALLS — The mysterious Native American petroglyphs carved into the rocky banks of the Connecticut River at Bellows Falls — while an enduring source of fascination — have long been misunderstood.

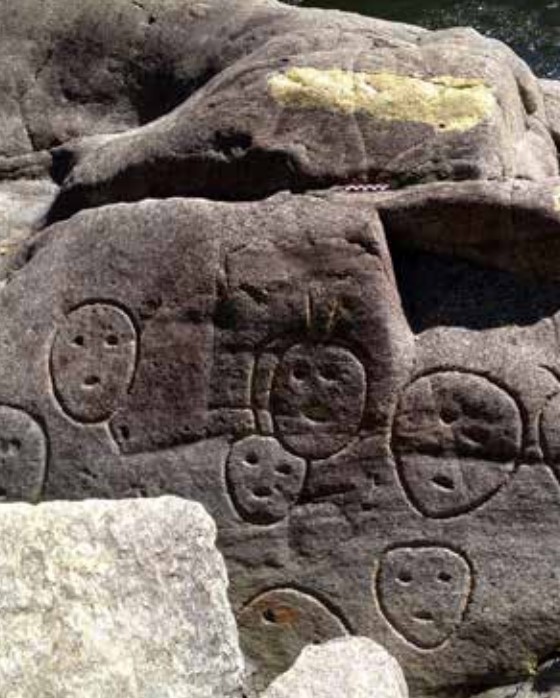

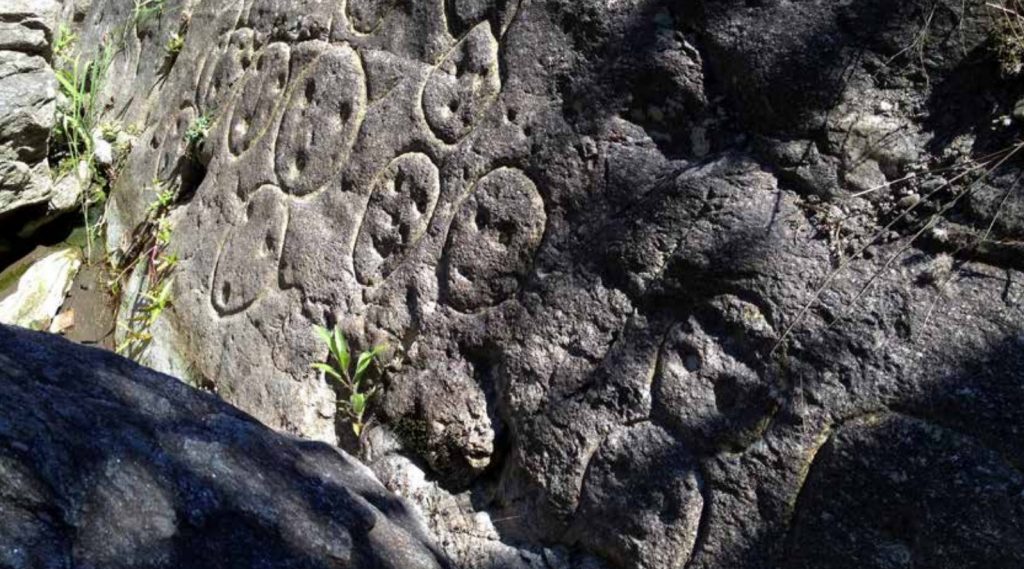

The petroglyphs, numbering about 24 faces, are believed to be about 3,000 years old. They are included in the National Register of Historic Places, but that posting is based on 1980s history and language, and unfortunately, prejudiced.

But a new movement, to correct the old record and biases, hopes to put the petroglyphs into the context of the sacred Abenaki ground and give them the recognition, and respect, they deserve.

Grant for underrepresented communities

The town of Rockingham and the Elnu Abenaki tribe joined forces to apply for a National Park Service grant for underrepresented communities, which would correct and expand the 1980s official record, with a more accurate and sensitive description of the petroglyphs and their role in the region.

In mid-April, the town received notice that it had received the grant of $36,832, one of 22 projects in 16 states across the country funded by the National Park Service, to better represent Black, Indigenous and communities of color. And the grant is the first such Park Service grant received by a Vermont community.

Rich Holschuh, director of the Atowi Project in Brattleboro, visited the Bellows Falls petroglyphs this winter, standing on the now-closed Vilas Bridge, which spanned the winter-subdued Connecticut River. He looked south, just over the railing to the petroglyphs below. Snow and ice covered one of the banks of petroglyphs. Another bank of petroglyphs is permanently covered with heavy stone rip-rap.

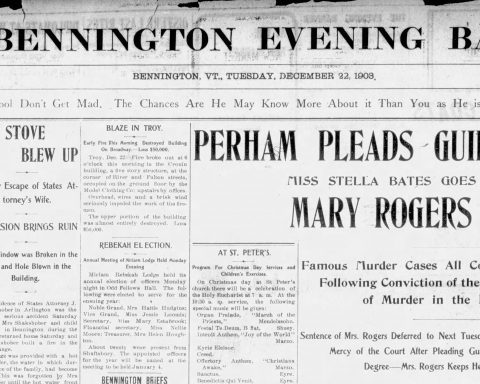

The Bellows Falls petroglyphs were first reported in the late 1780s, according to Lyman Simpson Hayes’ “History of the Town of Rockingham, Vermont,” when a Dartmouth College professor visited the site, and cautioned that the petroglyphs might be a warning of evil spirits. Misunderstanding has continued.

‘They are not art’

“They are not art,” said Holschuh, rejecting a common perception that the petroglyphs were created by indigenous people as part of an artistic expression.

They are deeply spiritual, he said, and The Great Falls mark an important spiritual home for the Abenaki community. Bellows Falls, or Kchi Pontegok, or The Great Falls in the Abenaki language, has been a key spiritual site for the Abenaki tribe for eons.

Even 1800s colonial history includes reference to Native American elders returning to Bellows Falls to die and to be buried there with their ancestors.

The petroglyphs were desecrated when the Daughters of the American Revolution hired someone back in the 1930s to re-chisel the petroglyphs, so they wouldn’t fade from the public’s easy view. It was done to maintain the petroglyphs as a tourist attraction. In the 1960s, the petroglyphs were painted yellow, so the curious could more easily find them.

More than faces carved in stone

Holschuch said the Bellows Falls petroglyphs are much, much more than faces carved in rock.

Holschuh, a former member of the Vermont Commission of Native American Affairs, is from Wantastegok, or Brattleboro. A descendant of both Mi’kmaq and European settlers, he’s one of the leading voices in Southern Vermont for indigenous people, and as a cultural researcher.

The Bellows Falls petroglyphs are better known than the recently re-discovered petroglyphs in Brattleboro, at the mouth of the West River, where it joins the Connecticut. They are the only known Indigenous petroglyphs in the state of Vermont.

The Brattleboro petroglyphs ended up about 15 feet below the river surface when the Vernon hydroelectric dam was built about 120 years ago. Local diver and historian Annette Spaulding of Rockingham uncovered them about six years ago, and they depict what is believed to be spiritual animals, such as birds, eels and dogs. The Bellows Falls petroglyphs, meanwhile, depict banks of elemental faces.

Ancient culture called this place home

The Abenaki, whose lands stretched from what is now New York state to downeast Maine and beyond, lived in this region of New England for 12,000 years and uncounted generations before European settlers came to this continent.

The two Vermont Abenaki petroglyph sites are sacred sites, Holschuh said, and are on the banks of rivers, with a mountain nearby, and where potholes were carved out of the rock by the rushing waters. He said there were reports of copycat carvings on the New Hampshire

Another bank of petroglyphs, similar to these, is permanently covered with heavy stone rip-rap.

side of the river, but they are not considered authentic because of their location.

Others might have disappeared because of heavy industrial use of the riverfront, Holschuh said.

The Great Falls site also was sacred, he said, because it is the narrowest section of the Connecticut River; in fact, it was the site of the first permanent bridge across the 450-mile length of the Connecticut.

The Bellows Falls petroglyphs were first reported in the late 1780s, according to Lyman Simpson Hayes’ “History of the Town of Rockingham, Vermont,” when a Dartmouth College professor visited the site, and cautioned that the petroglyphs might be a warning of evil spirits. Misunderstanding has continued.

Applied for grant in February

Walter Wallace, the town of Rockingham’s historic preservation officer, completed the grant application in February. He gained the official support of the town, as well as the property owner, Great River Hydro, to apply for the almost $40,000 grant.

Wallace said, because the town of Rockingham is a “certified local government,” in historic preservation parlance, it is eligible to apply for the National Park Service grant, while the Abenaki tribe is not.

Wallace has set up the grant so that it is co-managed by Holschuh and Gail Golec of Walpole, N.H., a local archaeologist, who has done extensive research into the Abenaki in the Bellows Falls area.

Wallace said the petroglyphs were included in a 1980s historic site nomination for a district that covered most of The Island area, a section of downtown Bellows Falls that was split off into an island with the creation of the Bellows Falls canal in the late 1700s.

The grant will allow the Abenaki and Rockingham communities to address cultural representation, inequalities and simply update the listing for that area of downtown Bellows Falls, Wallace said.

These faces are believed to be “elementals,” carved into the Bellows Falls rock by the Abenaki, which were then altered by the Daughters of

the American Revolution in the early 1900s.

Susan Smallheer — has been reporting for the Brattleboro Reformer since 2018. Before that, she was a reporter, statehouse reporter, bureau chief and editor for the Rutland Daily Herald in Vermont for many years. She lives on a small sheep farm in Rockingham.