As New England warms, the bloodsuckers come out to play and head farther north

By Gena Mangiaratti

Vermont Country

It’s an unsettling moment when you go to brush a speck of dirt off your skin, only to find it won’t brush off, and upon closer inspection, that said speck of dirt has legs.

Though a lifelong New Englander, I didn’t have this experience until adulthood, having likely picked up the little bloodsucker while trail running in Turners Falls, Mass. I found the tiny vermin latched onto the side of my head, and, up until the moment a friend of my roommate yanked it off with the smallest pair of tweezers I’d ever seen, I was quite certain it was sucking out my brains.

Now that I knew ticks were not just the stuff of folklore, I began checking myself after every trail run. I would go on to brush off countless deer ticks, also called black-legged ticks. A few years later, I had the pleasure of seeing what one looks like fully engorged — like a miniature balloon filled with pus — when I found one on a significant other’s cat. He did the honors of yanking it off the poor thing.

Tick takeover?

I assumed my more frequent encounters with ticks were because of my own migration into more rural areas, but others’ experiences and state findings show an increase in the disease-carrying critters in the Northeast.

Patti Casey, environmental surveillance program director with the Vermont Department of Agriculture, said tick counts have shown a “zig-zag” pattern over the past several years — up one year, down the next, and back up again — but the general trend is up. And each year, she said she and her colleagues find more ticks a little farther north and east.

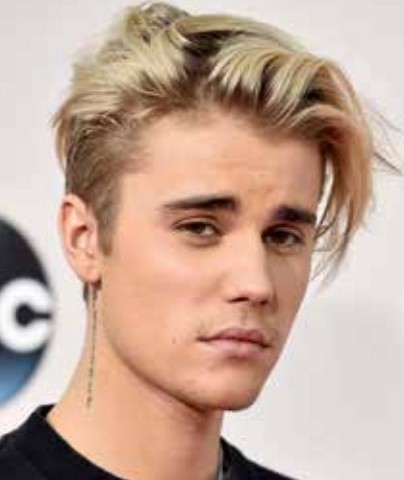

Even Justin Bieber had Lyme disease. “It’s been a rough couple years but (I’m) getting the right treatment that will help treat this so far incurable disease and I will be back and better than ever,” said Bieber in 2020.

“I grew up in the Champlain Valley, and I don’t remember, as a kid, any ticks, and I was outdoors all the time,” she recalled.

Experts say the increase in ticks could be attributed to climate change. With more frequent periods of warmth during the winters, ticks have more opportunities to emerge and find hosts when their predecessors might have died off.

“There’s just a lot more opportunities for them to be successful as a population than there used to be,” Casey said. “It’s one more thing about climate change that is, you know, not particularly helpful.”

So far, Casey said tick counts for this year are around the same as the year before, but advises continued vigilance.

Kelly Price, Brattleboro-area state game warden, noted that the still-chilly days of early spring are not too early to take caution. Ticks come out as soon as temperatures go above 40 or 50, he said, and he called their current disease load “really high.”

“I can’t emphasize enough to the public to not only be aware of ticks and the quantity of ticks we do have, but to protect yourself with permethrin,” an insecticide applied to clothing and gear, he said. He also reminds pet owners to treat their animals with tick and flea preventatives.

“Tick safety and tick awareness is so important, and I don’t see enough of it,” he said.

The black-legged tick is to be blamed

About 99 percent of tick-borne illnesses reported to the state are caused by the black-legged tick. A total of 15 species of tick have been identified in Vermont, six of which are known to bite and transmit Lyme and other diseases to humans, according to the Vermont Department of Health.

A black-legged tick, also known as a deer tick, rests on a plant.

About 54 percent of black-legged ticks are carrying the bacteria that causes Lyme disease — but Casey notes that there is a stark difference between pathogen prevalence and transmission rate.

“But that does not mean that you get a tick on you, you’ve got a 50 percent chance of getting the disease,” she said. “Transmission rate is actually fairly low.”

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection that is usually curable if treated early with antibiotics. Symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue and a bull’s-eye-shaped rash. If left untreated, the disease can spread to joints, the heart and nervous system, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After Lyme, anaplasmosis, also a bacterial infection, is the second most common tick-borne illness in Vermont, according to the Vermont Department of Health. Symptoms include fever, malaise, muscle aches, chills and headaches, according to the state.

How to stay safe

Casey said a black-legged tick must be attached for at least 24 hours before it can transmit Lyme disease. For this reason, she recommends daily tick checks on people and pets. She said ticks look for “hidden areas” on the body, such as between the toes or behind ears, which makes them harder to detect.

Other safety measures include tucking pants into socks and using an insect repellent. For those who are uncomfortable with using the chemical DEET on their skin, Casey recommends using an alternative that is EPA-approved.

When Casey comes in from looking for ticks for work, she immediately puts her clothes in the dryer on high to kill any that might have latched onto the fabric.

For Vermonters with yards, Casey recommends reducing log piles, brush piles and leaf litter, and staying on top of mowing.

“They typically aren’t in mowed grass. That’s not a big spot for them,” she said.

She also notes that ticks do not like to cross gravel or rocks.

A deer tick under a microscope in the entomology lab at the University of Rhode Island in South Kingstown, R.I.

Price said higher tick counts seem to be on south- or southeast-facing slopes or woods, and also in areas with dense deer and rodent populations. Once on a person or animal, he said ticks tend to travel upward on the body.

Price notes that for Lyme disease, the classic oval rash does not always occur, and advises contacting a medical professional if there are raised red marks or flu-like symptoms after any tick encounter.

For more information on tick species and preventing bites and illness, Casey recommends checking the Vermont Department of Health website.

“I feel like a lot of people are getting sort of afraid of going outdoors, and I feel really bad about that because I grew up here and am outdoors all the time,” she said. “I think it’s really important to say that we can absolutely still enjoy being outdoors.”

Gena Mangiaratti — whose first name is pronounced “Jenna” — is arts and entertainment editor for Vermont News & Media. When not newspapering, she can be found running, drawing and writing fiction. She lives in Brattleboro with her cat, Theodora.