By Felix Carroll

Against the backdrop of political assassinations, the Vietnam War, and the freakish slayings committed only a week before by the Manson family, Thomas Sadlowski grabbed his sleeping bag, stepped onto Route 8 in his native Adams, Mass., and stuck a thumb out.

His destination? A rock concert in the Catskills, something called the “Woodstock Music & Art Fair: An Aquarian Exposition.” He had seen a poster for it and figured, why not? Wouldn’t it be better than simply sitting on a bench in front of the American Legion on Park Street contemplating how civilization seemed beyond recovery?

“There was so much negativity at the time,” recalls Sadlowski. “Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot and killed. Charles Manson destroyed our childhood innocence with the brutal murders of the Tate family that August. We all just needed something positive.”

For Sadlowski and many other residents of the region who live to tell about it, Woodstock delivered.

Held 50 years ago, on Aug. 15-18, on Max Yasgur’s 400-acre dairy farm in Bethel, N.Y., the festival attracted more than 400,000 people and 32 of some of the greatest musical acts that rock music has ever known.

It didn’t take long for a car to pull over for Sadlowski that August day in 1969. A former high school classmate of his was also en route to Woodstock, along with some of her friends.

“Hop in,” they said.

A couple of hours later, there he was at Woodstock, an 18-year-old with no idea at the time that he was witnessing history.

Among those in the crowd was Andrew McKeever, who had just graduated that spring from Mount Anthony Union High School in Bennington, Vt. He recalls piling into a Chevy Impala with three of his buddies and heading south to Bethel, having no inkling of how Woodstock would change his life.

“I found out about it from reading the Village Voice,” he recalls. “I was most interested because I saw that Creedence Clearwater Revival was on the bill, and I said, ‘I’ve got to go.’ ”

Future Stockbridge resident, future Southern Berkshire District Court judge and future publisher of The Eagle, Fredric Rutberg, was also there. He heard about the concert while listening to the radio in his Greenwich Village apartment. He sent money in the mail, and four tickets eventually arrived.

Rutberg, who traveled to the concert from a summer rental in Tyringham, Mass., was a long-haired Vietnam War protester at the time. His most indelible memory of Woodstock wasn’t the concert itself. Rather, it was walking the country road toward the concert site. He and three of his fellow concert attendees passed through a neighborhood of Hasidic Jews. The Hasidic men, known for their distinctive appearance with their long, dark overcoats and long, uncut sidelocks, looked at Rutberg and his scraggly cohorts like they had come from another planet.

“They’re looking at us with eyes wide open,” recalls Rutberg, “the way they were used to people looking at them — like, ‘Who are these strange people walking in our neighborhood?’”

Rutberg, a late arrival, staked a spot high up on the side of a hill and way in the back, while down below, prowling amid the crowd with bags of camera equipment, was Benno Friedman, of Sheffield, Mass., on assignment for Playboy and Seventeen magazines. Playboy wanted photos of the bands. Seventeen wanted photos of the kids in the crowd. Friedman, in retrospect, wished he could have cloned himself. The gig proved stressful and grueling but remains his most favorite photo assignment in a long and distinguished photo career.

“I had no sense of the enormity of it all before I got there,” Friedman recalls, “and certainly I didn’t realize the impact of the festival on the culture going forward. I was just psyched about the assignment, of having an ‘in’ to this mega concert.”

Indeed, it was mega. The concert was intended for a crowd half the size The attendees from the Berkshires and Vermont each noted a great advantage they had from the outset. Because they were coming from the north, they avoided that infamous 10-mile-long traffic jam on the northbound lanes of the New York Thruway reported to have lasted the entire festival.

“We slipped right in and found parking about a half-mile away from the show,” says McKeever.

While Woodstock would, indeed, prove a pivot point against the violence and disorder of the times, in the moment, it all seemed like something much simpler.

“It was a bunch of kids who got together and just wanted to hear some music,” says Sadlowski, now a retired social worker for the commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Still, Sadlowski notes, something special seemed afoot. He said he spent much of the festival walking around, people-watching. What did he see?

“A lot of friendship, goodwill, sharing — an idyllic atmosphere,” says Sadlowski, who would soon begin his sophomore year at Bridgewater State University that September. “There was just a lot of camaraderie. We became a family.”

He ate lentils for the first time. A stranger invited him to sit out Saturday’s epic rainstorm in a car in order to remain dry.

For McKeever, Woodstock made it official for him: He was no longer part of mainstream America. He was a searcher in a world gone wrong — and clearly, he wasn’t alone.

“Going to Woodstock and seeing all these other young people was like, ‘Oh, there’s this whole other world out there beyond the confines of Bennington, Vt.’ ” says McKeever, who lives in Sunderland, Vt., and works as the news director of GNAT-TV. “It broadened my outlook on a lot of things. I guess the fact that there were a lot of people like me — that they actually existed — many of them further along the spectrum than I was, it all felt reassuring, reinforcing.”

For a time after the concert, McKeever refused to wash the jeans he wore that were caked in sacred Woodstock mud. He wishes he still had those jeans today as a memento.

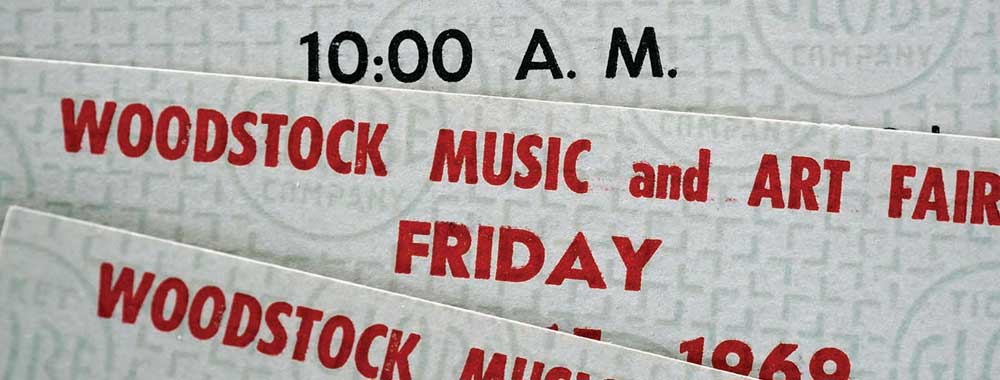

Rutberg has his momentos — his Woodstock tickets themselves, since concert organizers never got around to collecting them. He keeps them with his other valuables — his passport and car title — in a locked cabinet.

Yet memories of the music itself still serve as the most cherished monument for most Woodstock attendees. Think about it: Richie Havens, Arlo Guthrie, Joan Baez, Santana, Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Sly & the Family Stone, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, The Band — just to name a few.

For Friedman, whose photos wound up gracing the official Woodstock live album that was released in 1970, the highlight was the closing act: the nearly two-hour-long Monday morning set by Jimi Hendrix, including his rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

By that time, the crowd had begun leaving. The field was a wreck.

“People were bleary-eyed,” says Friedman, who made his way to the stage as he heard Hendrix’s guitar. “The garbage, the soaked clothing — it had the feeling of something extraordinary having happened there, like a war or something. And here was this extraordinary music coming across the field. It was the equivalent of someone playing an organ in a giant cathedral full of people who had taken refuge there and had nothing.”

The Hendrix set is the one thing McKeever would rather not discuss.

He missed it. Because he had to get to work on Monday morning, he and his buddies left Sunday morning, after Jefferson Airplane’s set.

“My main regret was that I didn’t think to just call in sick for Monday,” he says. “We were all too responsible. I’ve been kicking myself. Aye Yaii Yai.” •

Felix Carroll is a freelance writer who makes his home with his family in the Berkshires.