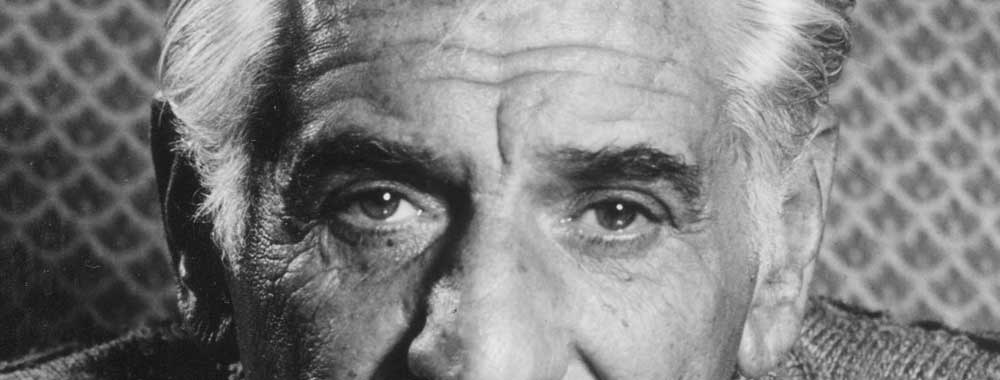

By Andrew L. Pincus

In Tanglewood’s crumbling, now disused Theater-Concert Hall, Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa were sitting side by side in the audience at a student concert.

During intermission, a boy in a Red Sox cap came down the aisle and asked Ozawa for an autograph.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra director happily signed the boy’s program, then pointed to Bernstein and asked the boy, “What about him?”

“I don’t know him,” the boy said, and disappeared.

The kid had yet to learn: Bernstein was larger than life, overshadowing even a Tanglewood icon like Ozawa. Nobody could be around Tanglewood on a daily basis in those years without encountering Bernstein, and nobody could be around Bernstein without getting scorched.

At Tanglewood, he was alumnus, scion, conductor, composer, pianist, teacher, mentor, genius, polymath, god — and nobody knew it better than he. He was a member of the inaugural class of the Tanglewood (then Berkshire) Music Center, 1940, becoming a protege of Serge Koussevitzky.

On the verge of death in 1990, he conducted the BSO in the Koussevitzky Music Shed in his last concert anywhere. It was the sad farewell to a 50-year career as a fixture at Tanglewood and a citizen of the world.

He wasn’t known as “maestro.” He was “Lenny.”

In an opening address to the 1970 crop of students, Bernstein recalled how he had arrived at Tanglewood 30 years before “in a state of wild excitedness and anticipation.”

Koussevitzky was the polestar: “He was a man possessed by music, by the ideas and ideals of music, and a man whose possessedness came at you like cosmic rays, whether from the podium or in a living room or in a theater like this.”

Bernstein had other allegiances — the New York, Vienna and Israel Philharmonics high among them — but it was to Tanglewood that he returned nearly every summer to conduct, teach, party, revel among the young and be an all-round presence.

So it is fitting that the season-long retrospective of his compositions that Tanglewood is about to present is probably the grandest of the many tributes being paid around the world on the centenary of his birth. The climax of Tanglewood’s festivities and obeisances will be a gala on Aug. 25, the actual birth date. Classical and Broadway stars from his firmament will take part.

There was a precedent. In 1988, Tanglewood threw a four-day birthday blast for Bernstein’s 70th, culminating in a nearly four-hour gala. The celebration laid to rest various squabbles and absences that had arisen over the years.

The low point came in 1981-82, when Bernstein, miffed by the BSO’s refusal to record Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” with him as conductor and pianist, boycotted the orchestra and festival.

Only Bernstein was privileged to wear Koussevitzky’s cufflinks and capes, to drive onto the car-free campus in an open convertible bearing the license plate “Maestro 1.” With an entourage of managers, assistants, press reps, family, friends and a housekeeper, he arrived for 10 days to two weeks like a king surrounded by his court.

His conducting classes at Seranak, Koussevitzky’s old mansion overlooking Stockbridge Bowl, were a well of wisdom — also, at times, the occasion for grandstanding for the young.

“I don’t tell you to do it this way,” he would say, in effect, while explaining how to conduct a passage: “Mozart tells you.”

Bernstein would then tell, with deep insight into both baton management and musical comprehension, how to do it his way. In his 1970 address, urging hope rather than despair during the morass of Vietnam times, he said it was up to the young, “with your new, atomic minds, your flaming angry hope, your secret weapon of art,” to save the world.

Koussevitzky, the avatar, was the BSO director and Tanglewood founder. Aaron Copland, the dean of the country’s composers, headed the music center for the first quarter-century. Bernstein, who returned as Koussevitzky’s assistant after the war in 1946, was quickly accepted as a member of Tanglewood’s founding trinity. Ozawa, who led the BSO 29 years, entered the pantheon but never on a rung with the founding three.

Koussevitzky died in 1951 without succeeding in having Bernstein anointed as his successor. Bernstein and Copland retained a close friendship until death.

Everything about Bernstein, whether his gifts or his appetites for cigarettes, drink, late nights and praise, was larger than life; only his height, which was exaggerated by his dynamism and visage — Adonis-like in his youth, rutted and wasted in old age — was ordinary. (Cigarettes finally led to his death.)

Concertgoers objected to his podium histrionics: the gyrations, the dance steps, the Dionysian gapes, grimaces and grins, the leonine head flung back, the levitations. But they were an emanation of the volcanic forces within.

Suppress his prancing or his extravagances, and you would suppress the 10,000-volt shock the music delivered. The man knew not only where music’s innermost secrets lay, but how to will musicians to go to those hidden places with him. He often said that when he conducted he became the composer. That of course gave him license to turn every composer into a Bernstein. Mahler’s obsessions became Bernstein’s; Bernstein’s, Mahler’s.

In politics he was forever tarred by Tom Wolfe’s “radical chic” label. Yet his liberalism was genuine, leading to a friendship with John F. Kennedy and a 1989 Berlin performance of Beethoven’s Ninth celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall. In Bernstein’s telling, Beethoven’s exalted summons to “Freude!” (joy) became one to “Freiheit!” (freedom).

The final concert took place on a gray Aug. 19, 1990, six days before his 72nd birthday. The program consisted of the Four Sea Interludes from Britten’s “Peter Grimes,” recalling the Bernstein-led American premiere of the great opera at Tanglewood in 1946;

Bernstein’s own “Arias and Barcarolles,” in an orchestration by one of his many proteges, composer Bright Sheng; and Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony.

Bernstein’s appearance as he walked unsteadily onstage was shocking: at once bloated and gaunt. His performance of the music for the death-fated fisherman Grimes had the grip of self-prophecy.

Unable to conduct his own work, he turned it over to another protege, conductor Carl St. Clair. Seized by a coughing spell, he had to cease conducting altogether in the third movement of the Beethoven symphony, leaving the orchestra to fend for itself.

After a frightening minute or so, he threw himself into the whirlwind finale as if to prove he still had the energy of old. A cigarette, and then oxygen, awaited backstage.

He didn’t have the energy of old. That night, a planned 12-day tour of Europe with the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra — the student orchestra’s first performances ever outside Tanglewood — had to be scrapped. It was to have been the culmination of summer-long festivities celebrating the 50th anniversary of the school from which he had emerged.

“In my end is my beginning,” Bernstein said, quoting T.S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” during the 70th birthday celebration in 1988. He was his own prophet.

On Oct. 14, 1990, six weeks after the final Tanglewood concert, he was dead. Copland followed six weeks later, on Dec. 2.

Tanglewood has not been the same since.

The Bernstein Centennial Celebration at Tanglewood

This summer, the Boston Symphony Orchestra pays tribute to Leonard Bernstein, celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth with a season-long theme at Tanglewood in Lenox, Mass.

On Saturday, Aug. 25, the birth date of the BSO conductor, a gala concert at the Koussevitzky Music Shed will span the breadth and depth of his career as a composer and maestro. Expect a bit of everything, from Bernstein’s “Candide” and “West Side Story” to a finale of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony.

For information on this program and other Bernstein tributes during the season, visit

tanglewood.org.

UpCountry also recommends cruising by the Celebrate Bernstein website at celebratebernstein.org. Here, the BSO has assembled a timeline of Bernstein history, filled with gems of information.

Andrew L. Pincus is The Berkshire Eagle’s classical music critic and the author of five books, including three about Tanglewood and musicians associated with it. As a freelance writer, he has written for The New York Times and other publications.