By Laurie Norton Moffatt

I attended a Town of Stockbridge Planning Board meeting one recent evening, when about 250 citizens from our small village of 2,500 came out on a cold winter night to learn about proposed changes to the town’s zoning bylaws.

The committee briefly outlined the issues and then invited citizens to queue and speak. About three dozen individuals waited patiently to speak over the two-hour meeting.

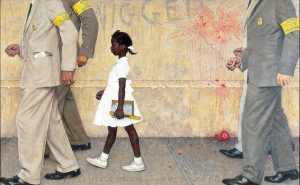

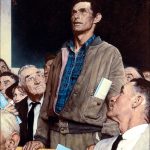

One citizen carried with him a large matted print of Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech painting, referencing the First Amendment right to freedom of expression, depicting the central Lincolnesque figure standing tall to speak his mind.

However, what he called to our attention were the dozen figures in the painting who, like the audience assembled, were respectfully listening and learning from the speaker, noting that to permit one to speak freely, it is essential that others must be willing to listen.

This is the essence of our democracy, and this is the essential quality in Norman Rockwell’s artworks that have made him beloved across the nation: his portrayal of community, gatherings of individuals who respect the people around them. Family, friends, strangers — Rockwell’s people are always kind. Sure, they enjoy a good laugh, sometimes a prank or a joke, but they are always respectful and courteous.

And interestingly, wherever Rockwell’s work is shown, people always think he represents their community. That is why he is equally at home in New England, the Midwest, South and West — and even internationally when his work has been shared abroad. We know him as our Berkshire neighbor and friend, from his hometowns nestled in the ribs of the Berkshire Hills and Green Mountains of Arlington, Vt., and Stockbridge, Mass.

But he was a true citizen of the world and he loved people everywhere.

As public dialogue becomes increasingly discordant and polarized in recent times — intensified and broadcast by the unfiltered echo chamber of social media; as income inequality becomes ever-more extreme; and as the free press is subject to continual attack, the very notion of the common good, and of civic engagement and civil discourse — all of them central to Norman Rockwell’s work — are called into question.

Are they still relevant as organizing principles of civil society or have they joined the mores of a bygone era? Can we find anew an esprit-de-corps in our communities or are we destined to devolve in outrage and stridency to impose one’s views over another?

The United States of America was founded upon passionately held beliefs and contentious issues, ranging from religious freedom, to the rejection of taxation without representation, to individual liberty, to the pursuit of wealth, among others. The nation was shaped by both the Greek and Roman ideals of sovereignty by the people and a colonizing philosophy derived from a notion of European entitlement that included slavery and the appropriation of land from indigenous peoples. These are not foundational premises of harmony and accord.

Indeed, the establishment of founding principles for the new nation was fraught with controversy and discord: The Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights were the products of fierce intellectual debate by our nation’s Founding Fathers.

Can the America of today truly come together in common cause? Are there binding principles or beliefs around which a majority of people can agree? Or is this simply an idealistic notion of a peaceable kingdom? Is respectful discourse with the free expression of ideas merely a utopian ideal framed in the Bill of Rights?

Civic engagement, thoughtful discourse, listening, tolerance and a sense of community, whether on the local or national level: These are themes that Rockwell turns to again and again in his artworks. He does so explicitly in his painting, “Golden Rule”: Do unto others as one would have them do unto you. Here, peoples of all religions, races and ethnicities live together in harmony, bound by the fundamental premise of universal humanity and respect. In this aspirational image, Rockwell paints what I believe was his personal philosophy of love for all peoples as a single, common humanity.

How did he come to portray the ideals of universal human goodness? It started with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s rhetoric describing four essential freedoms.

The Four Freedoms

President Roosevelt was confronted simultaneously with both the domestic crisis of the Great Depression and the urgency to go to war to defend our ally nations and secure freedom around the globe. Mobilizing Americans behind a war on foreign soil while they were struggling to recover not only from the Depression but also from World War I was among the greatest challenges of his presidency.

In striving to put forth a set of values that Americans could rally around, Roosevelt articulated four universal freedoms — Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear — as rights that everyone, everywhere, should enjoy. While the first two of these rights are embedded in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights, the other two were among the goals of the president’s aspirational and controversial New Deal, intended to provide a social safety-net for Americans through Social Security and other government-supported programs. They remain widely debated even today.

Roosevelt and his administration had a difficult time garnering attention and support for the Four Freedoms. They appealed to artists to give them visual form, hoping to create a compelling narrative of the necessity of America’s entrance into World War II. Few of these efforts resonated with the public, however.

In the meantime, Rockwell, wanting to support the war effort (and perhaps also spurred by regret that he had been too young to contribute to the World War I poster campaign organized by the Society of Illustrators), retreated to his studio in the tightly knit New England community of Arlington, Vt., to ponder how to visually communicate the “big idea of freedom.” After much introspection, he decided to express these enduring ideals through familiar genre scenes of everyday community and domestic life, his common and universally beloved subjects.

The Four Freedoms paintings are compelling expressions of Rockwell’s ideals of respect, courtesy, tolerance, generosity, caring and community, and they helped Americans find common ground at a time of world peril.

The paintings were not only an immediate success, garnering public support for the war effort and claiming their place among the most indelible images in the history of American art: They were also a turning point for Rockwell himself, who thereafter remained attuned to calls for social justice.

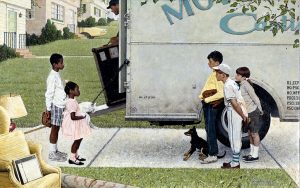

Over the next two decades, he aspired to paint images that tackled big ideas, such as “United Nations” (whose founding charter was framed around the Four Freedoms series); the “Golden Rule” cover image for the Saturday Evening Post; and three powerful paintings, commissioned by Look magazine, documenting the Civil Rights Movement, when America faced head-on the climb toward freedom and equality for all.

America was and is imperfect, and Rockwell was aware that many Americans did not enjoy the freedoms he attempted to illuminate. Roosevelt’s enduring ideals, expressed in the Four Freedoms, were a call to do better in America and across the world. They awakened in Rockwell a desire to use his artist voice to seek justice for all people.

Can these paintings once again remind us of what it means to be American — to be generous, inclusive, kind, respectful, forgiving, nurturing, brave and virtuous? Will these paintings inspire America and the world to a return to the ideals of civic virtue, civic engagement and civility?

Or is it unrealistic to think that these images can bring a sense of common purpose and unity to a nation fiercely divided over notions of human rights and social justice, engaged in a drama played out in the increasingly angry national debate over immigration, race relations, taxation, health care, education, stewardship of the environment and America’s diplomatic role in the world?

Norman Rockwell came to know the power of his artistic voice through the Four Freedoms paintings. He became an artist activist in the second half of his life, using his position as an elder statesman and plying his brush and canvas to advocate for human rights. His artworks may speak to us more powerfully today than any time since their creation. His art invites a return to “Main Street,” another of his iconic images, where we know our neighbors, from the local lunch counter to the barbershop; we develop a sense of community and caring for each other. Whether a village Main Street or a bustling urban block, community happens where people come together and know each other as neighbors.

“Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt and the Four Freedoms,” a traveling exhibition of these seminal paintings, will bring the images that rallied Americans to the defense of freedom across the globe to a broad public in the United States and on the 75th anniversary of the Allied landings in France.

These are four of the most important and influential images in American art. These paintings brought the country together in defense of universal human rights. They mobilized a nation to act in defense of freedom around the globe. These images convey Rockwell’s respect for community, for civic engagement, for tolerance and careful listening. They hold out hope that a set of common values can bind a nation or a community.

It is my hope that Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms and his powerful artworks advocating for generosity and equality will once again inspire people to join in common cause for greater public good and remind us that it is as important to listen as it is to speak. Therein lie the ties that form our community bonds of respect and caring for each other, whether in the literal town square or our virtual social communities.

These artworks still hold a story for our times.

Laurie Norton Moffatt is director and CEO at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass.