By Rebecca Sheir

Of all the historic sites in the Berkshires, 87-year-old Wray Gunn of Sheffield, Mass., finds one particularly humbling: The Stockbridge Cemetery.

“When I go in there I feel like, ‘I’m associated with these people?’” he says. “I don’t feel like I’ve done that much!”

In the 1940s, Gunn was the first African American to play University of Massachusetts basketball. He became a respected chemist. But he feels his achievements pale compared with those of his ancestors – many of whom are buried in Stockbridge Cemetery.

One of them is free-born Stockbridge resident Agrippa Hull. Hull was a Revolutionary War veteran and among the region’s first African American entrepreneurs. His grave is in the southwest corner of Stockbridge Cemetery. His oil portrait hangs in the Stockbridge Library.

The cemetery and library are among 48 sites on the Upper Housatonic Valley African American Heritage Trail, which recognizes local African Americans who have made their marks in the region, country and world.

Even though African Americans make up just 2 percent of the Berkshires’ population, history professor and trail co-director Frances Jones-Sneed notes that “in almost any historical period from slavery down through the civil rights movement, you could name famous African Americans who had lived in the Berkshires and made a national and international impact.”

The problem, she says, is most people can only name a few – if any.

Winding through 29 towns in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Upper Housatonic Valley African American Heritage Trail seeks to change that.

Du Bois Homesite

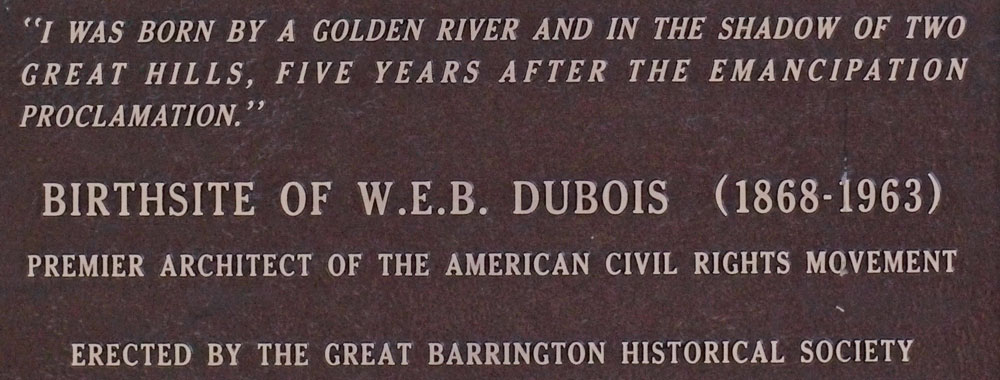

“I was born by a golden river and in the shadow of two great hills, five years after the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Thus begins the autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois, the father of the modern civil rights movement.

That “golden river” Du Bois was “born by” in 1868 was the Housatonic. Although the legendary author, educator and activist traveled the world, he proudly hailed from Great Barrington, Mass. The heritage trail includes more than a dozen sites associated with Du Bois, including the W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite, now a National Historic Landmark two miles south of downtown Great Barrington.

When Du Bois wrote about his boyhood home in 1928, he called it “a delectable place – simple, square, and low, with the great room of the fireplace, the flagged kitchen, half a step below.”

What’s left of that “delectable place” are fragments of the chimney and foundation, tucked away in a pine grove dotted with interpretive signs detailing Du Bois’ life and accomplishments.

It’s one of several heritage trail sites that’s more memory than museum. Du Bois’ birthplace is another, marked solely by a bronze plaque on Church Street. Likewise with the boyhood homesite of James VanDerZee, the leading photographer of the Harlem Renaissance. His childhood house in Lenox has made way for an empty space beneath the Route 7 bypass.

But Frances Jones-Sneed believes the condition of these sites doesn’t diminish their power.

“It’s sacred space that you are walking on,” she says. “These people have been there. You’re standing on the same ground that they stood on. It’s the connection of human spirit across generations.”

The Mumbet Story

One trail site that has stood the test of time is the Col. John Ashley House in Sheffield, which offers guided tours on summer weekends. The oldest house in the Berkshires, it’s where Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman was enslaved more than three decades. You can view an exhibit about her inside a small barn on the property.

The story goes that Bett, as she was known, overheard Col. Ashley and his colleagues draft the Sheffield Declaration of 1773: a statement of grievances against English rule. It inspired her to visit esteemed lawyer Theodore Sedgwick.

“Sir,” she said, “I heard that paper read yesterday, that says ‘All men are born equal and that every man has a right to freedom.’ I am not a dumb critter; won’t the law give me my freedom?”

Sedgwick accepted the case and Bett became the first slave in Massachusetts to sue for her freedom and win.

She took the name Freeman, and worked as the Sedgwicks’ housekeeper and nanny. The children loved Bett as a mother (“mum”) Hence her nickname: “Mumbet.”

Upon her death in 1829, Mumbet was buried in the Sedgwick plot near the Stockbridge Cemetery. Carved on her tombstone is an epitaph written by one of the Sedgwick children. It includes the words: “She could neither read nor write; yet in her own sphere she had no superior nor equal … Good mother, farewell.”

History as a guide

Because many sites along the Upper Housatonic Valley African American Heritage Trail lack signage or a physical structure, navigating can be a challenge. You can download a series of maps and guides on the trail’s website. And most local libraries carry “African American Heritage in the Upper Housatonic Valley,” a 230-page book describing sites on the trail and beyond.

In the introduction, Frances Jones-Sneed writes: “Very little is known about most of these people, even within the valley, yet their story is an important part of the national story of freedom, democracy and equality of which all Americans can be proud.”

But the descendants of these great individuals might be proudest of all.

Wray Gunn speaks fondly of his uncle: lumber dealer and land speculator Warren H. Davis. Davis felled and hand-hewed the impressive timber beams at Jacob’s Pillow in Becket, Mass. Jacob’s Pillow is on the trail, as is Davis’ former home in Great Barrington.

Gunn’s father, David Lester Gunn, became the nation’s first African-American prep-school athletic director and chaired the local NAACP. The David L. Gunn and Sinclara Hicks Gunn Home in Stockbridge is on the trail, along with the NAACP’s Berkshire County Chapter in Pittsfield.

But beyond his own family, Wray Gunn admires all the African Americans who’ve made history in the Upper Housatonic Valley.

“We’re so fortunate to have had prominent blacks living along this trail,” he says. “We all think that they should have been recognized and made more visible than they were.”

And now that they have been, he adds: “It’s a nice feeling.”

Five points of interest along the Upper Housatonic Valley African American Heritage Trail

The Rev. Samuel Harrison House

(Pittsfield, Mass.)

Not long ago, the city of Pittsfield planned on razing the dilapidated home of the outspoken abolitionist who became chaplain of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment (the Civil War division depicted in the movie “Glory”). The Samuel Harrison Society raised funds to restore the rundown building and now gives tours during the summer months.

Lee Memorial Hall

(Lee, Mass.)

In the Housatonic River Valley you’ll find numerous monuments to the men (black and white) who went to battle in the Civil War. The Lee Memorial Hall contains the most prominent: a plaque in the main hall that includes 54th Regiment soldiers from Lee.

Rosseter Street/Elm Court

(Great Barrington, Mass.)

This part of downtown Great Barrington was home to many African American families from the 1920s onward. Land speculator and lumber dealer Warren H. Davis resided at 11 Rosseter St., currently the Great Barrington office of WAMC public radio. The nearby Sunset Inn was a guesthouse predominantly used by African Americans including W.E.B. Du Bois.

And back in W.E.B. Du Bois’s old stomping grounds, a site in Great Barrington hopes to meet a similar fate.

Clinton African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

(Great Barrington, Mass.)

Built in 1857, it’s the oldest African American church building in Berkshire County. It fell into disrepair after its first female pastor, the Rev. Esther Dozier, died in 2007. Wray Gunn is heading up efforts to purchase and restore the building.

W.E.B. Du Bois River Park and Garden

(Great Barrington, Mass.)

Du Bois’ lifelong advocacy on behalf of the environment is among his lesser-known achievements. This pleasant park on the east end of Church Street includes a rain garden where storm water from the street is collected and cleansed by wetland plants before making its way to the river. The site pays tribute to Du Bois’ lifelong love of the Housatonic River and the natural elements of the Berkshires.