Ski Bum Rum’s Ryan Max Riley once skied the slopes as part of the U.S. Ski Team

By Mike Walsh

NORTH ADAMS, Mass.

The pretty butterfly with dirty blond hair has no idea how close she came to not having the opportunity to meet the handsome stranger dressed loosely in a chicken suit.

Chances are good that neither one knew exactly where they were, or who the gentleman behind the bar mixing drinks was, either.

It’s Saturday night in North Adams, Halloween weekend actually, and Ryan Max Riley is whipping up Blackberry Brambles and Old Fashioneds as quickly as his skilled hands will move. With every concoction, Riley dips in a clean spoon and tastes his creation before handing it over to the costumed customer.

Ryan Max Riley is a bit of a perfectionist, but he is a bit of a lot of things.

For one, he is a two-time national champion in men’s moguls who spent seven years on the U.S. Ski Team.

For another, he’s a self-employed master distiller who founded his own small business around his Ski Bum Rum.

“After [skiing on the World Cup] I had this plan of moving to Switzerland and finding an uninhabited hut in the Alps and living there with a goat, and being like a ski guide,” Riley said, jokingly — but only kind of — a week later in Pittsfield.

To those who mosied over from the Greylock Works Halloween party down the hall, though, he’s just the guy with light, salt-and-pepper hair, a button-down and jeans serving them drinks at a one-room nook off the back end of their masquerade with a big smile.

The two things of note are, one, the giant, floor-to-ceiling alembic pot still, shining in brilliant copper behind Riley, and two, the drinks he is making are ridiculously delicious.

The chicken guy all but casts aside the Blue Moon can he came in with, while a certain reporter in a white tank top and gloriously thick Freddie Mercury moustache quickly sips a Bramble.

I met Ryan briefly that night; with the Halloween party just beginning, it was going to be a long night for him. But it wasn’t the drinks or DJ down the hall that brought me to the renovated warehouse on State Road in the upper left corner of Massachusetts.

What the butterflies and Spider-Men and Steves from “Stranger Things” don’t know about their Saturday night is the incredible story behind how that bartender came to be in that spot.

Riley’s resume, if it actually existed anywhere, is impressive to the point of near intimidation. For whatever it’s worth, a Wikipedia page — he claims that it is horribly out of date — lists an overwhelming curriculum vitae that precedes the wiry 40-year-old chatting with the barista at Dottie’s Coffee Shop about the seasonality of the shop’s beverages.

Curriculum vitae is a term that seems befitting for a man whose academic history includes stops at Harvard, Yale and Oxford. He uses words like terroir to describe his gin, and has traveled the world honing his old and new trade.

It’s not hard to believe that the man whose side hustle is teaching a course on J.R.R. Tolkien at Williams College once persuaded his high school principal to let him attend classes one day a week while he skied the other four.

Riley still managed straight A’s.

But Ryan Max Riley isn’t some snooty academic. He’s a world-class athlete and master distiller.

Riley is only recently a Berkshire County guy, but he has spent the past year immersing himself in the area fully.

He grew up in Colorado and started skiing at age 11, and in short order his parents couldn’t drag him off the mountain. Eventually, they purchased a condo at a resort, and Riley would live there mostly on his own, eating SpaghettiOs, ordering pizza and fostering that goat-in-the-Alps idea.

This began a love of the ski lifestyle and the solitary meditation it provides. Eventually, Riley was sent to the Lowell Whiteman School (now Steamboat Mountain School), a prep school that allowed him to attend classes in the mornings and ski in the afternoons, with Fridays off to travel to weekend races.

“I was such a student of the sport,” Riley says. “Notebook after notebook of my scribbled handwriting trying to figure out how to become a better skier. I’d watch slow-motion videos every night. So, I got really good and made it onto the U.S. Ski team right after I graduated.”

At 15, he was the best skier in Colorado for all age groups, earning himself a spot on the North American tour, which is the level below World Cup. He won that and punched his ticket to the big time.

Riley’s first World Cup race was March 14, 1998, at Altenmarkt-Zauchensee, Austria. The 18-year-old placed 13th in men’s moguls, an event won by Jonny Moseley.

He spent the next seven years on the U.S. national team, winning a pair of national championships. He had no desire to go to college, instead craving the travel. But, a broken back altered his perspective, and a better backup plan was needed.

Ryan Max Riley. Photo by U.S. Ski & Snowboard

Ryan Max Riley, center, on the podium at the 2004 U.S. National Championships in Heavenly, Calif. Photo by U.S. Ski & Snowboard

Riley shows off his skills in Blackcomb, Canada, 1999. Photo provided by Ryan Riley

In 2002, he was accepted and started attending Harvard University, while still skiing moguls for the United States.

“I had to fly a lot more than my teammates, back and forth every week or every other week,” he says. “I would drive to the World Cup in Mont Tremblant in Quebec, and Lake Placid, but beside that, it was flying. Every Monday you pretty much flew to another country.”

The solo drives and flights just presented more solitude for the guy who used to wear big, baggy jackets and ski pants so he could fit books in the pockets to read on chairlifts.

Riley’s time on Team USA coincided with the founding of what is considered “new school” and freestyle skiing.

Contemporaries like J.P. Auclair, who died in an avalanche in 2004, and J.F. Cousson are responsible for fostering the sport as we now know it.

“I was right around the origin of that. These guys I would ski moguls with were the founders of new school,” says Riley, who calls Cousson the godfather of new school.

“We spent summers together going to arcades and causing trouble, then we’d be skiing and J.F. would be trying these things like Misty Flips, and we didn’t even know what a Misty Flip was, it was crazy.

“He’d just throw his body off a jump, do an upside-down 720, which seemed so dangerous. Then we started experimenting doing mute grabs and tail grabs and inverted maneuvers.”

On the SkiBumRum.com website, there’s a Sierra Ski Times magazine cover of Riley doing an iron cross tail grab off a jump. It’s from January 1999, not long after Moseley’s 360 mute grab won Olympic gold at the Nagano Games in 1998.

“It was such an exciting sport because we were sort of figuring out new tricks,” says Riley. “People were just figuring out how to do 360s with an iron cross. Now, it’s so basic, but hardly anybody could do that stuff. There was such possibility, it seemed like a really exciting moment in the sport with a lot of potential for doing things that nobody had ever been able to do before.”

After his career as a professional skier came to a close in the mid-2000s, academic pursuits took hold for a time, and he collected degrees from Harvard and Oxford, while writing for the National Lampoon and making plans to tackle the Ph.D. program at Yale.

Somewhere in there, he met a girl named Emily and shifted gears once more. Riley left Yale to start his own business, a micro distillery.

What was once a pursuit of skiing excellence, then literary, became rum, and now, gin.

“I’m a skier, so I wanted to make a rum specifically designed for winter cocktails,” he says. “I try to make my spiced rum smell and taste like Christmas. It’s really good in things like hot buttered rum, hot toddies and eggnog. It’s the perfect winter rum.”

It took seven years for Riley to perfect his silver rum; much of that time was spent while opening the Ski Bum Rum distillery in his native Colorado. He also has since added an award-winning coconut rum made with real coconut and vanilla bean, and sugar cane he imports from Mauritius, a small island in the Indian Ocean.

That kind of devotion is undoubtedly a holdover from the days of film study and notebooks full of diagrams from his time on the mountain.

“You do a lot of studying and drills, but then you get it and it becomes second nature. It’s really crazy what skiers can do after they’ve mastered it. Without even thinking, I can fly down a double diamond hill of moguls, dangerously fast, and then do a backflip with a 720 upside-down, land it and the whole time I’m not really thinking. I just kind of do it, like a strange animal,” Riley says.

He’s not bragging, but almost speaking stream-of-conscious in the third person. Skiing and distilling are topics he could talk about for hours, and you have to bear with him when the literary scholar pops in for an interlude.

And does he think he is getting to that “upside-down 720” point with his distilling and cocktail mixing?

“That’s exactly what it feels like, because it takes so long to figure out how to make outstanding silver rum. It’s the hardest thing you can possibly make. It’s like, in ancient Greece, one of the best displays of artistic talent was just to draw a perfect circle by hand. If you could draw a perfect circle, it meant you were a great artist. I think of silver rum like that. If you can make a really good one, it means you’re so good at distilling and fermenting and blending that you can make anything else.”

His first batch of gin was incredible, he says. His first batch of rum was far from it.

Every batch, like each trip down a mogul field, he tweaks, in a constant effort to be better and better until he can operate on instinct.

The gin experimentation started organically out of talking to local foragers.

He realized he could make a local craft gin that would taste unlike any other in the world. It also went somewhat hand in hand with Emily, now his wife, finishing her Ph.D. and getting a job as an English professor at a small school called Williams College in Northwestern Massachusetts.

Three years in, Riley had to load his whole setup onto two big trucks and move across the country. He rushed to get everything in and set back up before his 40th birthday in May. They started serving in October, and The Distillery at Greylock Works, Forager Gin & Ski Bum Rum, is open every Friday and Saturday from 5 to 9 p.m.

The transition certainly wasn’t seamless, but with it, Riley has refound parts of his youth.

“We really like this region, and we thought it was a good spot to move the business to because it is really similar to the Alps, where I wanted to move with my goat, and Colorado, where I grew up,” he says.

“It’s really mountainous, great skiing, incredible hiking. The forests, I think, are so incredible, they’re really old; some of these trees have never been cut down and there’s such interesting things growing in there. I’m a big forager; I love wandering around the woods finding things to use in my gin.”

Forager Gin is Riley’s newest product, and he plans to make one for each season, using ingredients he finds on hikes, always sustainably and respectfully, and sometimes with Emily and their St. Bernard. He is fascinated by the different trees he has found in New England, like black birch, for their aroma, and burdock root.

“I try to make so many things that would be really enjoyable next to a fire, during the winter when the snow is falling,” he says. “That’s one of the images I have in mind when I design certain cocktails.”

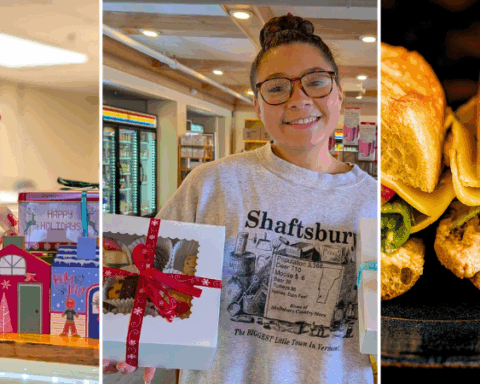

He has become part of a community with fellow foragers like Nicholas Moulton, executive chef at Mezze Bistro, and nearby Tourists’ Tracy Remelius.

In this respect, he feels a kinship with Tolkien.

“He is very important to environmentalists, he was way into trees and nature. He was kind of anti-industrial like I am,” Riley says.

“I was kind of upset that Denver is doing so well economically. I’m way more old-fashioned. I love the middle ages and crafts. That’s why I have a microdistillery, because I don’t want to build it for scale and sell it all over the country, and make it into something gigantic, like Bacardi. I just want to keep it small and focus on the craft and have it feel more like an alchemist’s shop.”

The bar inside Greylock Works does have that feel, with glass canisters of fresh ingredients — Riley forages in the morning and then adds ingredients to his gin that day — lining the top and a full glass storefront-style window into the hallway, where his miniature still sits for experimental batches.

“The reason gin is so appealing is, it uses botanicals, and every region has its own botanicals and indigenous plants and foraging knowledge,” he says. “There’s terroir in gin. A gin made in the Berkshires doesn’t taste like a gin made anywhere else.”

It’s a place that fits right into North Adams and the Berkshires as a whole, a place Riley embraces for its local feel.

“It’s a really interesting, temporal effect; skiing here feels very much like skiing in Colorado when I was a kid,” he says. “Skiing in Colorado feels different now. I think it was a little bit better when I was a kid. It’s like that here right now. It’s not as corporate. It’s more about the skiing and the people and nature.

“Less glitz and super-high-speed chairlifts and really expensive hamburgers.”

Riley somewhat laments the big-business culture that has taken hold in Colorado, groaning at things like Ferraris in ski resort parking lots.

“It’s a totally different culture, and it’s not the one I remember,” he says.

“This is more like what I grew up experiencing. It’s more off the beaten path. You don’t feel like the horses of capitalism surging around you all the time.”

With that, Riley is looking forward to experiencing more of the Western Massachusetts and southern Vermont ski scene. He has taken a volunteer position with the ski patrol at Jiminy Peak, and Emily alerted him to the Mount Greylock Ski Club’s rope tows. He also is intrigued greatly by Magic Mountain in Londonderry, Vt.

“It’s so uncorporate,” Riley says of Greylock. “That’s the kind of thing that can happen here in the Berkshires. It’s like what skiing would’ve been like 50 or 80 years ago. It’s that basic. All you really need for skiing is a really great hill and a way to get up it, like a rope, or you just hike up it. It shouldn’t be so expensive.”

They remind him of his youth at places like Arapahoe Basin, where you could tailgate in the parking lot.

“They’ve kept that original character. And that original character is all you need to enjoy skiing. When you start adding to that, you start detracting from the sport. If it’s just you, the slopes and your friends, and you didn’t have to pay a fortune for the pass and they’re not bombarding you with advertisements,” Riley says, thinking back on a World Cup stop in Japan, where they blasted a techno version of Beethoven’s Fur Elise on repeat.

“It’s really distracting and artificial. I like the classic skiing. Skiing in its raw state. The sport in its purest sense.

“What you should need to have an enjoyable life is just like a pair of skis and a couple of books.”

And a well-made apres cocktail doesn’t hurt, either. •

Mike Walsh is a sports writer with The Berkshire Eagle, where he authors the bi-weekly Powder Report column. He’s a bordering-on-30 snowboarder with a degree from Marist College and a natural curiosity for the finer things in life.