By Kevin O’Connor

By Kevin O’Connor

New Englanders may live amid trees spiked with sap taps, but anthropologist Michael Lange believes a majority are blind to their native sweet spot.

“Maple syrup is poorly understood by most of the people who consume it,” Lange says. “It’s even less understood by those who prefer artificially flavored corn syrup.”

That’s why the professor at Vermont’s Champlain College has poured years of research into a new book, “Meanings of Maple: An Ethnography of Sugaring.”

“There has been a wealth of academic attention paid to maple in the past, but it has looked at aspects such as the chemistry of the syrup, or the economics of maple sales, or the effects of sugaring on forest health,” Lange begins the 236-page volume. “Very little attention has been given to the cultural meanings and impacts of maple, and that is a gap I want to fill.”

“There has been a wealth of academic attention paid to maple in the past, but it has looked at aspects such as the chemistry of the syrup, or the economics of maple sales, or the effects of sugaring on forest health,” Lange begins the 236-page volume. “Very little attention has been given to the cultural meanings and impacts of maple, and that is a gap I want to fill.”

Lange wasn’t born an expert. As a child, the Midwest native thought syrup was something that came from a bottle.

“The first time I tasted real maple,” he says, “I remember it being interesting and different — and then I forgot about it.”

Lange was reacquainted when he joined the faculty of his Burlington-based college a decade ago.

“I have an interest in how people tell stories about their identity,” he says. “I needed to find a topic of research I could get into without plane tickets or time off.”

The professor was considering a study of community fundraising cookbooks when he noticed so many filled with recipes calling for maple.

“A lot of people know the standard narrative — 40 gallons of sap for one gallon of product — but I have run into some who think you drill a hole in a tree and syrup comes out.”

Sugar makers tell a different story.

“I quickly realized when they talk about maple, they don’t just talk about the product, they also talk about the tree, their family, their place — all these things together and how they influence each other. They talk about maple in a complex way.”

Such conversations start with taste.

“Because of this research, I’ve tried a lot more different maple syrups than most folks,” Lange says. “It has given me a culinary awareness I wouldn’t have had otherwise — and helped me pretend to have a discerning palate.”

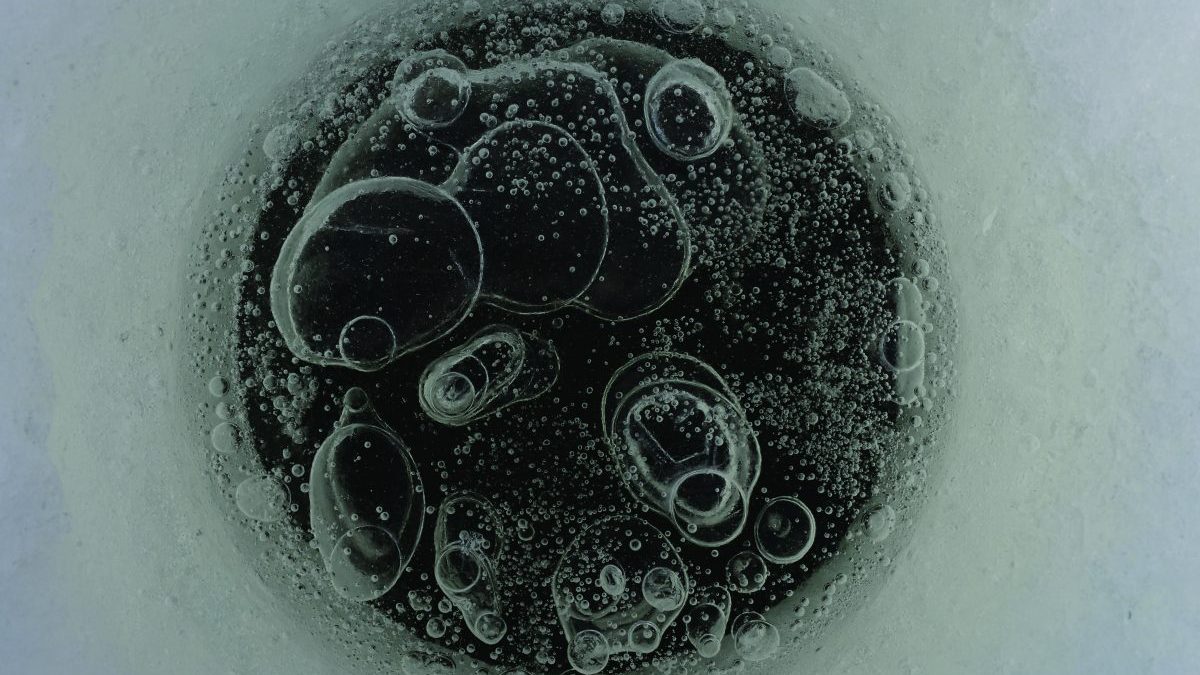

Next come questions of tradition versus technology. Does real syrup require metal buckets rather than plastic tubing? A steaming wood fire unsupported by a water-extracting reverse osmosis machine?

“Authenticity is a hugely complicated and often problematic concept. Where do people draw the line?”

Then there’s the subject of climate change. Sap flows when the weather teeter-totters between warm days and cold nights. But the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center, the oldest and largest such facility in the world, finds the sugaring season is starting “significantly earlier” than it did a half-century ago and its duration has decreased by an average of 10 percent.

“Sugar makers are a long-viewed bunch,” Lange says. “A lot think in intergenerational terms.”

The future, they know, could morph into a sticky situation if the region continues to feel the heat of global warming. For the author, the sum total isn’t a story of gallons, but instead one of reminding people “how systems interact,” be it on a farm, in a community or around the Earth.

“As an academic, I get to take all of this experience, wisdom and knowledge and put it together,” he says. “I have the side effect of being able to validate things. It makes people feel this topic is important.”

And so the author is promoting his book, published by, of all places, the University of Arkansas Press.

“There were others that showed interest,” he says, “but in academic publishing, you go with who says yes.”

Lange is receiving support from such fellow Vermonters as Bill McKibben, an environmental activist and author of the first book on global warming for a general audience.

“It’s about time maple syrup got the literary respect it deserves,” McKibben says. “The author has worked almost as hard to harvest his data as sugar makers work to gather March’s sap. Read it and you’ll never buy Aunt Jemima brand again!”

That said, Lange stresses his book isn’t an advertisement for maple, although he hopes it helps New Englanders see the importance of keeping the regional market sustainable.

“I try to get people thinking and talking,” he concludes. “The sheer variety of meanings that can be made with something as simple as a jar of syrup is obvious, but only if one looks.”

‘It is a personal story’

“Some forms of industrialization have been incorporated into the sugaring industry, but the family operation still dominates. When standing in the aisle of the supermarket, weighing the real maple syrup against the corn-based stuff, this idea is the first thing to remember. The corn-based stuff is made in an industrial factory somewhere that takes in truckload after truckload of corn or corn syrup. But real maple is very likely made by individuals who are tapping their own trees and boiling their own sap. It happens on a personal scale, which is why I think it is important to tell maple’s story. It is a personal story.”

— Michael Lange, from his book “Meanings of Maple: An Ethnography of Sugaring”

Kevin O’Connor is a Vermont native and Brattleboro Reformer contributor.