Vermont’s Robb Family Farm wondered if its future was past when it stopped milking cows after more than a century. Then Brooke Shields told People magazine about its maple syrup.

By Kevin O’Connor

If Hollywood ever chooses to turn the back-from-the-brink saga of Vermont’s Robb Family Farm into a feel-good holiday feature, it’ll need to cast actress Brooke Shields.

That’s because this true story improbably stars her.

Back in 1907, Thomas and Christine Betterley bought a Brattleboro farm a mile and a half up the dirt Ames Hill Road with hopes it would serve as their retirement pasture.

Five generations of descendants have toiled there ever since.

Father Charles Robb Sr., 81, and son Charles Jr., 52, can tell you about rising daily before dawn to milk 50 Holsteins at 5:45 a.m., then moving on to tend to barns, fan belts and fences and, to make ends meet, produce and peddle firewood (the younger was chain-sawing a beech tree in 2004 when a flyaway branch shattered every bone in his since-healed face), all before a second milking at 4:45 p.m. and sleep by 9.

Shoppers pay almost $5 for a gallon of milk, but the laborers who actually provide it can receive as little as a third of the retail cost — the main reason why the number of Vermont dairy farms dropped from 16,700 at the turn of the 20th century to less than 1,000 when the Robbs were forced to sell their cows six years ago.

“It’s like a death in the family,” Charles Sr. said of that fateful day.

“We haven’t died,” his daughter Mary replied in polite defiance.

And so sprang the question facing hundreds of dairy farms whose land forms the groundwork of Vermont’s $700 million agriculture industry and $1.5 billion tourist economy: Is shedding the past the way to save the future?

Following state calls for a 21st-century “working landscape” encompassing farming, forestry and production of everything from meat to solar and wind energy, the Robbs reseeded their cornfields with grass to raise beef cattle and added taps to produce maple products for their sugar-house gift shop and website, robbfamilyfarm.com.

Vermont may be small, but its maple business is big. The state is the nation’s largest syrup maker, with annual sales of more than $200 million accounting for 42 percent of all United States production.

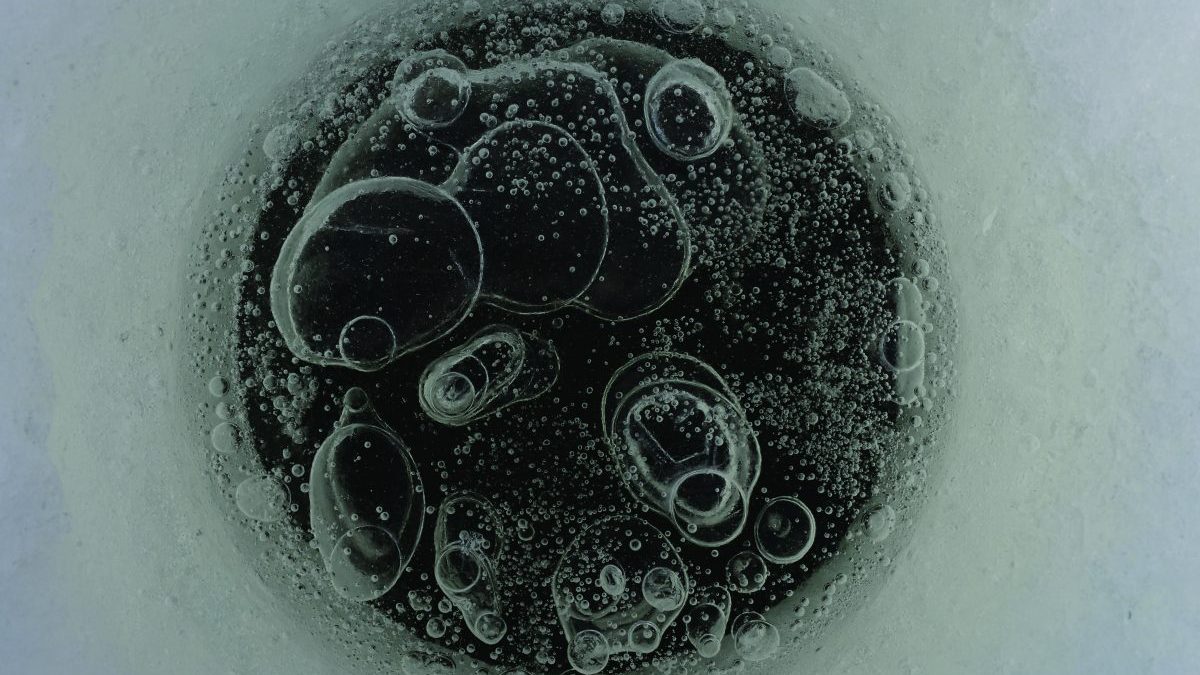

Robb Family Farm maple syrup features a century-old label. Photo by Kevin O’Connor.

Green Mountain output has more than doubled over the past two decades — in part because of technological advances. Reverse osmosis systems, for example, reduce the water content of sap, which, in turn, cuts boiling requirements. The Robbs, who make up to 85 gallons a day without such advances, are watching competitors pump out the same amount in about half the time.

“They’re making commercial sweetener, that’s my opinion,” Charles Jr. says.

“We’re trying to do it the old-fashioned way, so you’ve got to market it.”

But how? Just before last Thanksgiving, the farm received an email inquiry from People magazine.

Helen Robb showed her son the message.

“This could be something good,” Charles Jr. thought.

Sisters Laurie, Mary and Betsy, aware of phishing scams, countered it could be something bad. But two weeks later, family members turned to page 90 of the Dec. 5, 2016, issue and found Shields — a celebrity they’ve never met — recommending a $14.95 pint of their syrup as the perfect holiday gift.

“Within 24 hours, we began getting orders,” Helen says.

Make that coast-to-coast orders, first for pints, then half gallons, then gift boxes — so many, the family sold out the last of its supply by the time it started tapping again.

The Robbs still don’t know how or why Shields recommended their syrup.

They only see that a half-dozen years after the loss of dairy, the farm remains the stuff of a Currier & Ives print: white barns framed by green fields, red maples and, when the sun’s out, endless blue sky.

Helen’s the same, too. Shopping last holiday season, she came upon a small decorative sign proclaiming “Blessed Beyond Belief.”

“We have a pretty strong faith,” she says. “I thought, ‘We need that.’”

Then the equally frugal matriarch saw how much it cost — $14.95. Leaving empty-handed, she woke the next day with a change of heart. That’s why, when the family gathers for the holidays this year, all will see the sign — fortuitously the same price as what Shields paid for her pint — offering good tidings over the kitchen door.

“I have a hard time with change, but I was recently thinking, ‘God closes doors and opens doors,’” concludes Charles Jr., who’s aiming to add enough taps to nearly double the farm’s maple production. “It was tough seeing the cows go, but it was the best decision we ever made.”

Kevin O’Connor is a Vermont native and Brattleboro Reformer contributor.